Imagine you go to pay for your morning coffee and your stored-value card returns an error message, or the wallet in the payments app on your phone isn’t opening because the company providing the payment service has gone bankrupt. Worse, what if you live in a rural area and the e-money service provided through your mobile phone was the only access you have to the financial system? Or your government now relies on the e-money system to transfer benefits or collect taxes on a large scale?

Digital forms of money—including central bank digital currencies, privately issued stable coins, and e-money—continue to evolve and find new ways to become more integral in people’s day-to-day lives. In essence e-money is a digital representation of fiat currency guaranteed by its issuer. Customers exchange regular money into e-money, which they can use to make payments through an app on their cellphone to individuals and businesses alike with ease and immediate effect. Compared to other recently developed forms of digital money, such as stablecoins, e-money has been around for some time and its customer base continues to rapidly increase. Unlike most privately issued stablecoins, e-money operates in a regulated framework.

For regulators and supervisors charged with protecting consumers and ensuring a level playing field for all financial intermediaries, keeping pace with new developments can be challenging. Regulators and supervisors need to consider how to best protect customers from the failure of (potentially systemic) e-money issuers, including preventing the loss of their funds.

A new IMF staff paper considers these and other scenarios that may put consumers and—potentially—entire e-money systems at risk. We examine how regulatory practices are evolving on a country-by-country basis and put forward a set of policy recommendations on regulating e-money issuers and safeguarding their customers’ funds.

E-money offers payment solutions for the unbanked

We can think of e-money as an electronic store of monetary value on a prepaid card or an electronic device, often a mobile phone, that may be widely used for making payments. The stored value also represents an enforceable claim against the e-money issuer, by which its customers can demand at any time to be repaid the funds they used to purchase e-money.

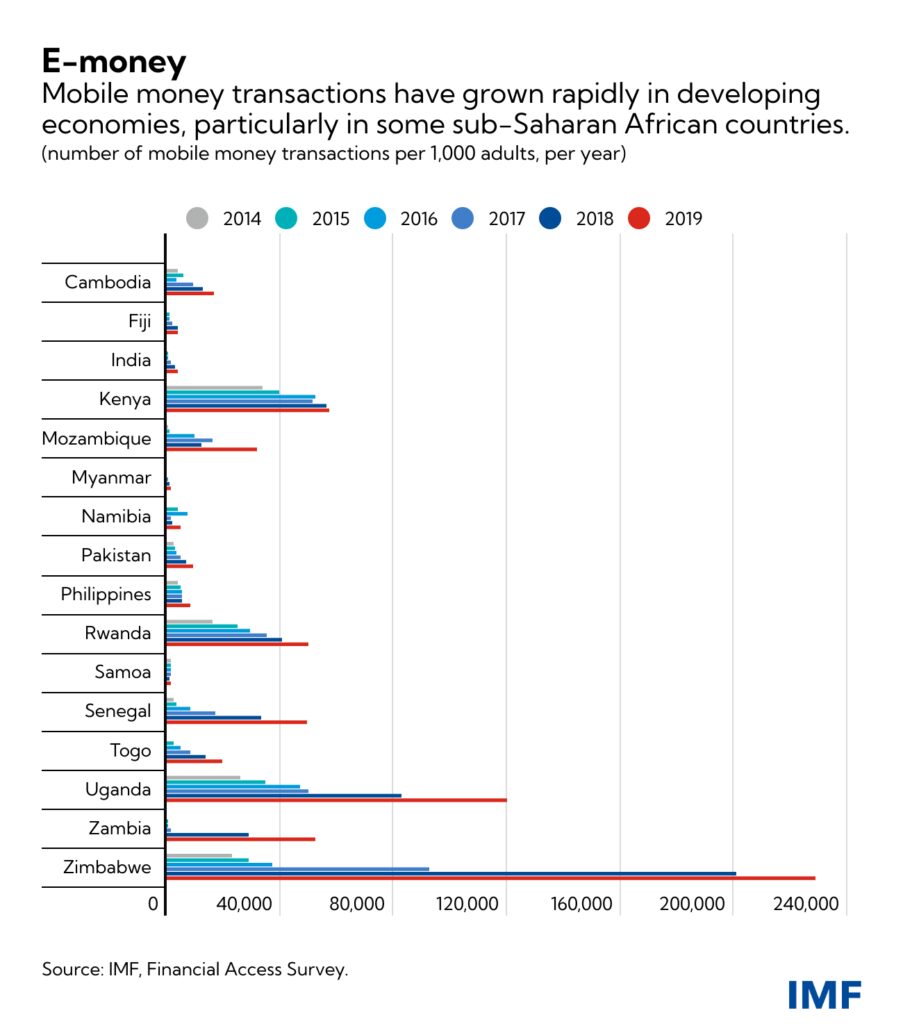

E-money is already a vital part of daily life for billions of people, especially in many developing countries, where many lack access to the banking system. As shown in the chart below, a high percentage of the population across a number of East African countries now use e-money, making it important from a macro-financial perspective. It is estimated, for instance, that two-thirds of the combined adult population of Kenya (where M-PESA has reached a high degree of market penetration), Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda use e‑money regularly. Many of these people do not have bank accounts or other access to the formal financial system, so they store significant shares of their disposable funds in e‑money wallets and access them using mobile phones or computers.

Protecting financial systems and consumers alike

With the growing importance of e-money issuers, a comprehensive, robust framework for regulation and safeguarding customer funds is critical. Issuers should be subject to proportionate prudential regulatory requirements. For example, they should establish operational risk governance and management systems to identify and limit risks. They should also be prohibited from retail lending. And, in order to protect consumers who may be less sophisticated than bank customers, rules should be put in place governing how issuers disclose fees, protect consumer data, and handle complaints.

One of the most important regulatory measures identified in our paper is that in order to protect customers’ money, all e-money issuers need to implement mechanisms to safekeep and segregate those funds. Issuers need to maintain a secure pool of liquid funds that is equivalent to the amounts of customers’ balances, and which is kept separate from the issuer’s own funds. This is a fundamental safeguard against misuse of the funds and should allow, in principle, for recovery of those funds in the event of bankruptcy of an issuer.

Keeping the customers’ funds segregated, however, does not resolve all the problems if a potentially systemic issuer were to fail. In the absence of specific bankruptcy rules, segregation by itself does not ensure that the customers would get quick access to their funds, and this discontinuity may create severe problems if the issuer plays a potentially systemic role in the payments system and in day-to-day transactions of the country.

Potentially systemic, potentially problematic

Regulators and supervisors may need to significantly strengthen prudential oversight and user-protection arrangements, depending on the business model and size of the e-money system. In countries with a potentially systemic e-money issuer or sector, the protection in place should seek to preserve customers’ funds and ensure continuity of critical payment services.

While some countries have sought to extend deposit insurance to e-money, further efforts may be needed to operationalize such protection and ensure that it would work effectively in practice. In particular, customers should not lose access to their funds and, therefore, services should be restorable or replaceable quickly, preferably within hours. But putting e‑money deposit insurance into practice remains untested so far—at least in practical terms. The costs and benefits of extending deposit insurance coverage effectively to e-money should be carefully considered.

As with many issues in the fintech sphere, best practices are still taking shape, making policy decisions challenging. However, the pandemic has only increased the importance of prudent e-money frameworks, as the number of online transactions and e-money’s growth has accelerated. For regulators and supervisors, the time for action is now.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News