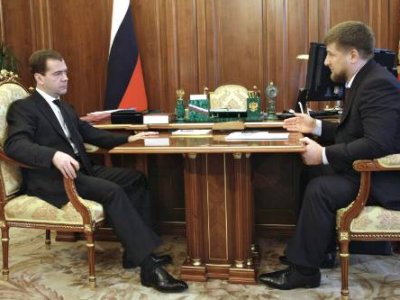

Chechen President Ramzan Kadyrov said he had been ordered by Russian President Dmitry Medvedev to fight insurgents in the neighbouring region of Ingushetia after its leader was gravely wounded in a bomb attack.

Chechen President Ramzan Kadyrov said he had been ordered by Russian President Dmitry Medvedev to fight insurgents in the neighbouring region of Ingushetia after its leader was gravely wounded in a bomb attack.

Kadyrov’s harsh tactics have brought relative stability to Chechnya since he was elected in 2007 after more than a decade of war. But fellow Kremlin appointees have failed to stem spikes in violence in neighbouring Dagestan and Ingushetia.

With Ingush President Yunus-Bek Yevkurov fighting for his life in hospital, Kadyrov said he had been ordered by Medvedev to run cross-border operations.

“He told me to intensify actions … including in Ingushetia,” Kadyrov said in an interview with Reuters. “I will personally control the operations … and I am sure in the near future there will be good results.”

Yevkurov was appointed in October to replace Murat Zyazikov, who was accused of fanning the insurgency with heavy-handed measures. But the situation has deteriorated, with a series of high-profile attacks over the past three weeks.

Yevkurov was badly wounded on Monday when a suicide bomber by the roadside destroyed his armoured Mercedes car. Russia’s Vesti-24 channel said investigators believed it was a female suicide bomber whose name had been established.

Medvedev visited Moscow’s Vishnevsky Institute of Surgery where Yevkurov, 45, was being treated late on Monday.

“He has received serious injuries and as a result, a whole host of organs are damaged, above all the skull. The rib cage and liver are also damaged,” Vladimir Fyodorov, the institute’s director, told Medvedev. “His condition remains grave … he is on artificial respiration.”

‘THERE WILL BE BLOOD’

Analysts say Kadyrov’s past as a rebel has helped him. But human rights groups say he has achieved relative calm by pushing violence underground, kidnapping and torturing suspected rebels and burning the houses of their families.

“If they used torture and detentions (in Ingushetia) there wouldn’t be any Wahhabism, terrorism,” Kadyrov told Reuters. “It is the lack of action of certain leaders,” that is to blame.

He said cross-border operations with Yevkurov had achieved considerable success, killing over 30 rebels in recent months.

Accompanied by an entourage of 20 in the lobby of Moscow’s President Hotel, Kadyrov rejected the criticism of his heavy-handed tactics as naive.

The rebels “don’t have any humanity,” he said. “We will take no captives, we will destroy them. As long as they exist there will be blood.”

Kadyrov, whose father was killed in a rebel bomb attack in 2004, said he had no sympathy for families of rebels who refuse to give up their relatives.

“We are sick of protecting them … They are accessories in Wahhabism, terrorism,” he said, tapping the table with his fist.

Kadyrov accused Western rights groups of caring more about the fate of terrorists than the innocent people of Chechnya.

“When they kill me, when they kill my father, when they kill thousands of my people, everyone stays quiet, but if a ‘devil’ is beaten while being detained, straight away there is an outcry.”

Analysts have linked the growing unrest in the North Caucasus with a fall in resources from the Kremlin to buy off local leaders, and have suggested Chechnya’s recent stability could be threatened by a cut in hand-outs from Moscow.

“Nothing has changed,” Kadyrov said. “On the contrary, we have strengthened our position in 2009, the federal centre is helping us more.”

Kadyrov also rejected accusations he had created a cult of personality in Chechnya, where almost every street is decorated by vast posters of Kadyrov and his father.

“Kadyrov has created constitutional order and straight away they start talking about a cult of personality,” he said.

“I am a servant of the people. Ask anyone ‘who is Kadyrov?’ in the remotest regions, in the mountains, if they don’t cry with gratitude for what we have done for them, I will sign my resignation in front of you.”

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News