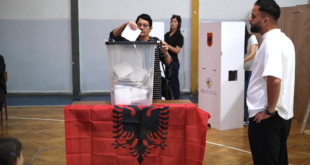

FOR months the opinion polls suggested that Albania’s election would be close. Most pundits said they were wrong, because respondents were giving unreliable answers. Now Albanian opinion polling has come of age. So close was the June 28th election that, four days later, the result was still unclear. Albania faces weeks of election challenges and political horse-trading—and perhaps even a fresh election in the autumn.

The poll pitted the prime minister, Sali Berisha, who has dominated Albanian politics ever since 1990, against the mayor of Tirana, Edi Rama. Both Mr Berisha’s centre-right Democratic Party and Mr Rama’s Socialists have alliances with smaller parties. With almost all votes counted, Mr Berisha was claiming 71 seats in the 140-seat parliament, but Mr Rama’s party hotly disputed this.

Mr Berisha campaigned on his government’s achievements since 2005. The economy has done well. Last year GDP growth was 6.5%, and even in this year of world recession it is expected to be positive. In April Albania joined NATO and formally applied to join the European Union. New roads have been built, including a major highway to Kosovo.

Mr Rama has achievements of his own in Tirana, which is much improved from the chaotic place it once was. He has painted Mr Berisha as a demagogue in charge of a deeply corrupt government, arguing that it is time for a change. Yet Mr Berisha also talked of change. In fact, both men were coy about specific policies. They agree on the main issues facing the country: job creation, visa-free travel for their citizens and faster European integration. The issue for voters was whom they trusted most.

Given the drama and violence of Albania’s political life since the collapse of communism, and the corruption of some politicians, this election was the first that could be considered normal, says Remzi Lani, a political analyst. It was Albania’s first “vote of choice not of protest”. But the prospect of an equal balance in parliament makes it hard to see a stable government being formed, says Erion Veliaj, leader of the small G99 party. Albania might have to have a new election in a few months’ time.

This is not what the country and the wider Balkans need. This week Croatia’s prime minister, Ivo Sanader, unexpectedly stood down, raising new questions over how soon Croatia might actually get into the EU. Most other western Balkan countries have much further to go. Albania is the poorest of the lot. The IMF has given warning that Mr Berisha, in a bid to secure votes, has rushed to finish big projects such as the road to Kosovo, running up a dangerous budget deficit. Remittances from the quarter to a third of Albanians who live abroad have dropped sharply. A construction boom has turned to bust. Thousands of new flats are empty and brand new blocks of unsold ones line roads out of Tirana, Durres, Vlora and other towns.

Zef Preci, an economist and former minister, cautions that although Albania is not in recession, it may be soon. “The real challenge is not the decrease of remittances,” he says. “It is the return of emigrants which has not started.” He also notes that the 1930s Depression hit Albania several years later than other countries. Whoever runs the next government will find the job a tough one.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News