L’AQUILA, Italy

L’AQUILA, Italy

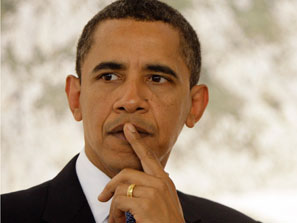

President Barack Obama and his aides were on the defensive at the G-8 summit here Thursday after developing countries attending a 17-nation climate change forum refused to commit to specific goals to reduce their output of greenhouse gases.

Taken together with a G-8 statement Wednesday that sidestepped any serious pressure on Iran to give up its nuclear ambitions, Obama in Italy has faced the reality of global summitry – that it has been difficult for him to translate his personal popularity at home and abroad into concrete action on two of his top priorities.

Obama tried to spur the climate-change talks by making a clean break with what he suggested was the United States’ record of dragging its feet on efforts to tackle global warming.

“I know that in the past, the United States has sometimes fallen short of meeting our responsibilities. So, let me be clear: Those days are over,” he said, speaking to reporters just after the Major Economies Forum meeting wrapped up. “One of my highest priorities as president is to drive a clean energy transformation of our economy, and over the past six months, the United States has taken steps towards this goal.”

Obama also tried to accentuate the positive by noting other climate-change developments, such as an agreement to seek to limit global warming to no more than 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit—a level beyond which scientists predict particularly severe impacts on weather, coastlines and agriculture.

Obama said the announcements represented important progress towards a larger United Nations meeting in Denmark this December where diplomats will try to create a new global treaty to address climate change.

“While we don’t expect to solve this problem in one meeting or one summit, I believe we’ve made some important strides forward as we move towards Copenhagen,” Obama said. “For the first time, developing nations . . .agreed to take action to meaningfully lower their emissions relative to business as usual in the midterm — in the next decade or so.”

Obama and other U.S. officials stressed that many of the pledges or statements were unprecedented, but many of them were also amorphous. It was unclear, for instance, what would constitute a “meaningful” reduction. And the nations did not adopt a target date after which global emissions must start falling.

Obama said the developing nations had agreed to “negotiate concrete goals” for carbon reductions before the Copenhagen summit, but the declaration from Thursday’s forum stopped short of promising to set such a number by December.

The White House’s point person on climate change, Todd Stern, said the vagueness of some of the commitments was not particularly noteworthy because the statements were not legally enforceable.

“Look, these are all principles that are getting articulated, so none of this is exactly binding on either side right now,” he said. “But it sets up measures that would go into an ultimate agreement. They have never done that. That’s a quite significant undertaking.”

Stern also defended Obama’s decision to acknowledge what he views as past errors by the United States on climate change —a practice which some Republicans have derided.

“I think that it is important for the United States to recognize where it has fallen short. Clearly we have an historic responsibility with respect to the emissions that are already up there in the atmosphere,” Stern said.

One of the most concrete pledges to come out of this week’s meetings was an agreement by the Group of Eight developed nations to reduce their carbon emissions by 80 percent by 2050. They also endorsed a goal of a 50 percent global reduction in carbon output by that year. While ambitious in their goals for four decades from now, the developed countries failed to set specific goals for carbon cuts in the near-term. And on the key issue of financing, the forum declaration contained no dollar figures. Instead, the countries observed that such investments “will need to be scaled up urgently and substantially.”

The lack of detail in those pledges may have contributed to the decisions by developing countries to balk at setting specific emissions limits. China, India, and other nations have said they are unwilling to take actions that could slow their economies in order to solve a problem created in large part by industrialized nations. Yet, without China and India, any effort to scale back greenhouse gases is likely to be ineffective.

The slow pace of the action on climate issues at the G-8-related sessions drew a rebuke from the United Nations Secretary General, Ban Ki-Moon.

“The policies that they have stated so far are not enough, not sufficient enough,” he said Thursday. “This is politically and morally imperative and a historic responsibility for the leaders for the future of humanity, even for the future of planet Earth.”

In Obama’s remarks on the climate change issue Thursday, he said he believed that the economic slowdown had complicated the negotiations.

“It is no small task for 17 leaders to bridge their differences on an issue like climate change,” he said. “It’s even more difficult in the context of a global recession, which I think adds to the fears that somehow addressing this issue will contradict the possibilities of robust global economic growth.”

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News