The front-runner in a carefully vetted field is Ebrahim Raisi, a hardline judge seen by analysts and insiders as representing the security establishment at its most fearsome.

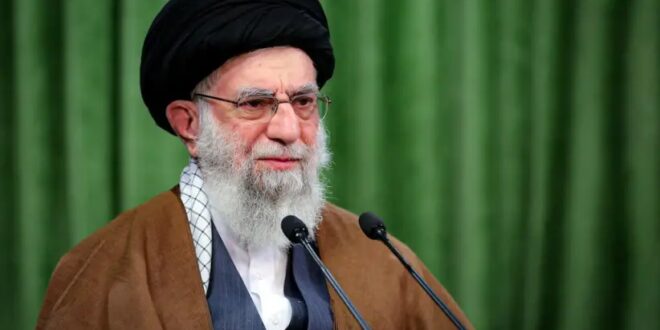

Iranians elect a new president on Friday in a race dominated by hardline candidates close to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, with popular anger over economic hardship and curbs on freedoms set to keep many pro-reform Iranians at home.

The front-runner in a carefully vetted field is Ebrahim Raisi, a hardline judge seen by analysts and insiders as representing the security establishment at its most fearsome.

But the authorities’ hopes for a high turnout and a boost to their legitimacy may be disappointed, as official polls suggest only about 40% of over 59 million eligible Iranians will vote.

Critics of the government attribute that prospect to anger over an economy devastated by US sanctions and a lack of voter choice, after a hardline election body barred heavyweight moderate and conservative candidates from standing.

The race to succeed President Hassan Rouhani, a pragmatist, will be between five hardliners who embrace Khamenei’s strongly anti-Western world view, including Raisi and former nuclear negotiator Saeed Jalili, and two low-key moderates.

The limited choice of candidates reflects the political demise of Iran’s pragmatist politicians, weakened by Washington’s decision to quit a 2015 nuclear deal and reimpose sanctions in a move that stifled rapprochement with the West.

“They have aligned sun, moon and the heavens to make one particular person the president,” said moderate candidate Mohsen Mehralizadeh in a televised election debate.

While the establishment’s core supporters will vote, hundreds of dissidents, both at home and abroad, have called for a boycott, including opposition leader Mirhossein Mousavi, under house arrest since 2011.

“I will stand with those who are tired of humiliating and engineered elections and who will not give in to behind-the-scenes, stealthy and secretive decisions,” Mousavi said in a statement, according to the opposition Kalameh website.

Mousavi and fellow reformist Mehdi Karoubi ran for election in 2009. They became figureheads for pro-reform Iranians who staged mass protests after the vote was won by a hardliner, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, in a contest they believed was rigged.

EXECUTIONS

If judiciary chief Raisi wins Friday’s vote, it could increase the mid-ranking Shi’ite cleric’s chances of eventually succeeding Khamenei, who himself served two terms as president before becoming supreme leader.

Rights groups have criticized Raisi, who lost to Rouhani in the 2017 election, for his role as a judge in the executions of thousands of political prisoners in 1988. Raisi was appointed as head of the judiciary in 2019 by Khamenei.

However, Iranians do not rule out the unexpected.

In the 2005 presidential vote, Ahmadinejad, a blacksmith’s son and former Revolutionary Guard, was not prominent when he defeated powerful former president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, largely seen beforehand as the frontrunner.

“(Saeed) Jalili’s chances to surprise us should not be underestimated,” said Tehran-based analyst Saeed Leylaz.

Although publicly Khamenei has favored no candidate, analysts said he would prefer a firm loyalist like Raisi or Jalili as president.

The election is unlikely to bring major change to Iran’s foreign and nuclear policies, already set by Khamenei. But a hardline president could strengthen Khamanei’s hand at home.

Iran’s devastated economy is also an important factor.

To win over voters preoccupied by bread-and-butter issues, candidates have promised to create millions of jobs, tackle inflation and hand cash to lower-income Iranians. However, they have yet to say how these promises would be funded.

All candidates back talks between Iran and world powers to revive the 2015 nuclear deal and remove sanctions.

But moderate candidate Abdolnaser Hemmati said hardliners sought tension with the West, while conglomerates they control rake in large sums by circumventing sanctions.

“What will happen if the hardliners come to power? More sanctions with more world unanimity,” Hemmati, who served as central bank chief until May, said in a televised debate.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News