The armed group has emerged as a strong player as US-led foreign forces pull out of Afghanistan after 20 years.

The Taliban have won a string of battlefield victories in recent weeks as the United States-led foreign forces are about to complete pull-out from Afghanistan after 20 years.

The armed group was removed from power in a US-led invasion in 2001 following the September 11 attacks on US soil, but it gradually regained strength, carrying out numerous attacks on foreign as well as Afghan forces in the past 20 years.

It managed to win some sort of international legitimacy after the US under then-President Donald Trump signed an agreement with the armed group on February 29, 2020, to withdraw foreign forces in exchange for security guarantees.

Trump’s successor, Joe Biden, did not reverse the troop withdrawal decision, instead, delaying it until September 11 to coincide with the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks. However, last month, he again revised that deadline to August 31.

Though the armed group largely kept its promise not to target US security interests, it continued to carry out deadly attacks against Afghan forces and civilians, saying the Western-backed Kabul administration was not a party to the February 2020 agreement signed in the Qatari capital, Doha.

The US-Taliban agreement paved the way for peace talks between the Taliban and the Afghan leadership. But the Doha talks have failed to make headway as violence has continued on the ground.

Since the Taliban launched a sweeping offensive against government forces in May, the armed group has taken control of crucial border crossings with Iran, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Pakistan.

With as many as 85,000 full-time fighters across the country, the Taliban now claim to control about half of the country’s roughly 400 districts. However, verifying such claims is difficult.

On Wednesday, the top US military general said the Taliban appear to have “strategic momentum” on the battlefield.

“This is going to be a test now, of the will and leadership of the Afghan people, the Afghan security forces and the government of Afghanistan,” Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman General Mark Milley told reporters at the Pentagon.

Hundreds of people have been killed and tens of thousands displaced due to the fighting, as Afghans fear the country might descend into civil war with peace talks in deadlock and the government’s accelerated push to arm local civilians to take on the Taliban directly.

On Friday, Taliban spokesman Suhail Shaheen said his group did not want civil war. He then insisted that for the Doha talks to succeed President Ashraf Ghani must resign.

“I want to make it clear that we do not believe in the monopoly of power,” Shaheen told The Associated Press news agency, adding that the armed group will lay down weapons after “a negotiated government acceptable to all sides in the conflict is installed in Kabul”.

Last week, Taliban chief Haibatullah Akhunzada called for a “political settlement” but his fighters have pressed ahead with military offensives against government forces.

Origin

The Taliban, which means “students” in the Arabic language, fought along the Afghan rebels called the mujahideen against Soviet occupation for nine years.

The US provided weapons and money to the mujahideen as part of its policy against the Cold War foe, the erstwhile USSR. At the time, the Soviets were backing the communist leaders who had staged a bloody coup against the nation’s first president, Mohammad Daoud Khan, in 1978.

After the Soviets pulled out in 1989, things turned chaotic, and by 1992, there was a full-blown civil war with mujahideen commanders fighting for power and dividing the capital city of Kabul, which would be showered with hundreds of rockets each day coming from different directions.

The Taliban militia emerged as a substantial player in 1994. Many of its members had studied in conservative religious schools in Afghanistan and across the border in Pakistan.

They made quick military gains winning control of Kandahar, the biggest city after Kabul, and promised to make the cities safe for people. Fed up with years of war, people generally welcomed them. The mujahideen commanders and their forces had been accused of rights abuses and war crimes in their competition for power.

By 1996, the Taliban had seized the capital and hanged the nation’s last communist president, Najibullah Ahmadzai, from a Kabul square. They declared Afghanistan an Islamic emirate and started imposing their own strict interpretation of Islamic law.

They were recognised by only three countries – Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Pakistan.

The Afghan group was able to bring a semblance of normalcy and took the decision to tackle endemic corruption, which won them some initial popularity.

Six-year rule

However, they never eased restrictions, which they initially said had been done to ensure that the crimes of the civil war could not be continued. Those restrictions included banning women from education and keeping all women, except for doctors, from working. Under their rule, anyone who did not follow their strict guidelines could be jailed or beaten publicly.

Their six-year rule was marked by abuse of ethnic and religious minorities and curb on seemingly innocuous activities and pastimes such as music and television. Even sports were highly regulated, as male athletes were told what to wear and matches were paused during the five daily prayers.

Their 2001 decision to destroy the historic Buddha statues in Bamiyan province drew global condemnation.

In 1999, the United Nations imposed sanctions on the Taliban for their links to al-Qaeda.

The US invaded Afghanistan on October 7, 2001, after the Taliban refused to hand over al-Qaeda’s leader, Osama bin Laden, who was hiding in Afghanistan after being initially invited back to the country by former mujahideen commander Abdul Rab Rassool Sayyaf.

In the lead-up to the US invasion, the group had asked the Bush administration to provide proof of bin Laden’s role in the 9/11 attacks and later for negotiations with Washington. Bush rejected both.

The Taliban were forced out of power within a couple of months as the US and its allies began a bombing campaign.

A new interim government headed by Hamid Karzai was formed in December 2001, and three years later a new constitution was promulgated, which took its cues from the reformed constitution of the 1960s, when women and ethnic minorities were formally granted their rights by the nation’s last king, Mohammad Zahir Shah.

But by 2006, the Taliban regrouped and were able to mobilise fighters in its battle against foreign occupiers and their allies.

The 20 years of conflict devastated Afghanistan, with more than 40,000 civilians killed in attacks by the Taliban and the US-led forces. At least 64,000 Afghan military and police and more than 3,500 international soldiers were also killed.

The US spent almost 1 trillion dollars on the war and reconstruction projects but the country still remains largely poor and its infrastructure in tatters.

In 2011, the Obama administration allowed for a group of Taliban officials to take residence in Qatar, where they would be charged with laying the groundwork for face-to-face negotiations with the government of then-President Karzai.

In 2013, their Doha office was formally opened. In 2018, the Trump administration began formal, face-to-face talks with the group without involving the Afghan government.

Parallel government

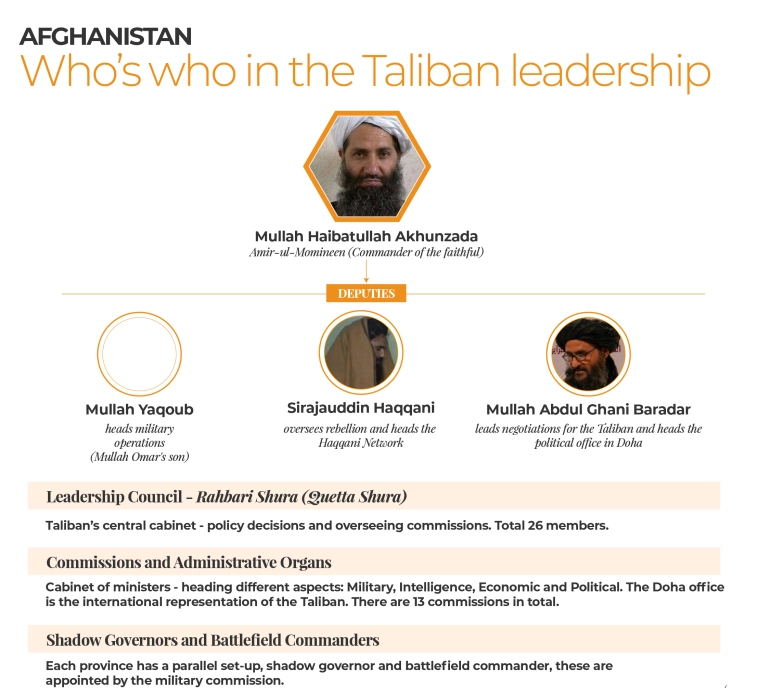

The Taliban have set up a parallel state calling it the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan with their own white flag. They have also selected shadow governors that have their own administrations in the nation’s 34 provinces.

The Taliban chief heads a council that oversees about a dozen commissions in charge of things like finance, health and education. They even run their own courts.

According to Taliban members and a UN committee, they make close to $1.5bn a year (PDF).

They have also earned revenue from partnering with local and regional mafias in the regional drug trade. Last year, they made millions from mining and trading minerals, and even producing methamphetamine (a stimulant widely used as a recreational drug) in partnership with regional mafias.

They also have their own tax collection system and receive funding from abroad – although suspected sources, like Pakistan and Iran, deny it.

Prospects for peace

The question now is – what will happen after US and NATO soldiers leave? Will the Afghan government be able to survive?

Even while peace talks have been going on – almost 1,800 Afghan civilians have been killed or injured in the first three months of this year. That is almost 30 percent more than last year.

The Taliban have also been blamed for a wave of assassinations targeting journalists and activists – a charge the group has denied.

According to a notable public opinion study (PDF) done in 2019 – 85 percent of people said they had no sympathy for them.

Afghans are already asking themselves what life might be like if the Taliban take over again. Will they rip up the constitution – which protects basic human rights?

In a New York Times op-ed, the Taliban tried to clear things up, saying it wants to “build an Islamic system … where the rights of women that are granted by Islam — from the right to education to the right to work — are protected”.

Shaheen, the Taliban representative, reiterated earlier this week, that “women will be allowed to work, go to school, and participate in politics but will have to wear the hijab, or headscarf”, a practice which is already commonplace in the current Islamic republic.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News