One of the most consequential changes in the Middle East’s geopolitical map is happening at the water’s edge. Along the entire eastern rim of the Mediterranean basin, global and regional actors are engaging in a spate of port capacity expansions, new private port construction, and the sell-off of major state-owned ports that will determine who sits atop the region’s global trade flows for decades to come. The international competition to rebuild Beirut’s port is one key puzzle piece in this larger process that is reconfiguring the Levant’s maritime commercial architecture and, as a consequence, the geopolitical contours of the Middle East.

The possibility that the Lebanese government could opt for China to reconstruct Beirut’s port has raised alarm in Washington and European capitals given China’s already outsized commercial port presence in Egypt, Israel, and Greece. Increased Chinese involvement in Lebanon’s port operations could consolidate Beijing’s hold over the commercial connectivity architecture of the Levant. Re-orienting global commercial flows between Europe, the Middle East, and Asia according to Beijing’s priorities would make China’s Belt and Road Initiative a dominant organizing principle in the international relations of the Middle East. The most effective way to offset China’s ambition may be to facilitate Mediterranean rivals France and Turkey to jointly rebuild Beirut’s port.

On Aug. 4, 2021, France, in conjunction with the United Nations, convened “The Conference in Support of the Population of Lebanon,” a video donors’ conference of 33 nations to raise emergency funds for an economically embattled Lebanon on the brink of financial collapse. The conference was held on the one-year anniversary of the massive explosion that devastated the port of Beirut, killing hundreds, injuring thousands, and affecting 300,000 Beirut residents. The conference succeeded in raising $370 million; France, with a pledge of €100 million ($118 million), and Germany, with €40 million ($47 million), were the leading contributions, along with the United States, with $100 million. While reflecting Lebanon’s overall strategic importance for Paris, Berlin, and Washington, the pledges also advance France and Germany’s respective bids to rebuild Beirut’s port and by extension the United States’ desire to ensure that China does not rebuild it.

Lebanon is in discussion with four countries about the Beirut port’s reconstruction — China, France, Germany, and Turkey — although other contenders like the UAE’s DP World have also expressed an interest in the project. Reflecting the urgency to return Beirut’s port to full capacity, France’s shipping giant CMA CGM made a $400-$600 million proposal back in September 2020 for reconstructing the damaged port infrastructure within a three-year timeframe, including some capacity expansion and a digitalization upgrade.

No matter which proposal is selected, CMA CGM will play a central role. One of the top 10 global port operators, the firm is owned by the French-Lebanese Saadé family, whose founder Jacques Saadé was born in Beirut and emigrated to France in 1978. The company is the Beirut port’s leading operator, handling 60% of its volume, and is the most amenable to public-private partnerships with the Lebanese government.

In contrast to CMA CGM’s approach, a consortium led by Hamburg Port Consulting (HPC) proposed an ambitious $7.2 billion urban renewal plan in April 2021 that would relocate the port and conduct major urban renovation projects, including the construction of residential areas, an outdoor park, and the creation of a new beach at the site of the destroyed port. Although the German plan requires a total timeframe three to five times longer than CMA CGM’s plan, the HPC-led proposal envisions creating 50,000 permanent jobs. CMA CGM has expressed its willingness to reconstruct the port itself as part of the German real estate development proposal, if invited to do so.

China’s growing strategic dominance over the Levant’s maritime architecture

Chinese construction and operation of the Port of Beirut would augment its growing dominance of the commercial maritime routes across the eastern Mediterranean. China already presides over the trans-Mediterranean, commercial maritime artery that connects Egypt’s ports to the European mainland at the massive Chinese-run trans-shipment port in Piraeus, Greece. Piraeus’s port operator China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) provides freight rail service that ultimately reaches Austria, the Czech Republic, Germany, and Poland.

China is assisting Egypt to increase the total container capacity of its Mediterranean ports to partner with Piraeus as the dominant trans-shipment hub in the Mediterranean basin. In a near mirror image to Piraeus, China occupies a preeminent position in both the operation of Egypt’s Mediterranean ports and their capacity expansion. The majority of Egypt’s foreign trade is handled by the Alexandria port and its auxiliary El Dekheila port with a combined container capacity of 1.5 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU). The port is run by Hong Kong-based Hutchison Port Holdings, as a joint venture between Hutchison, the Alexandria Port Authority, and Saudi Al Blagha Holding. Hutchison is also developing a 2-million-TEU Egyptian port at the nearby Abu Qir Peninsula that will start operations in 2022.

The 5.4-million-TEU Suez Canal Container Terminal (SCCT) at East Port Said is owned by Dutch-based APM (55%) and COSCO (20%) with the remaining 25% stake split among Egyptian entities and private sector participants. The SCCT services the entire Suez Canal Economic Zone mega-project, in which China is the largest investor. Although Egypt has successfully leveraged its relationship with China to attract considerable investments in transportation infrastructure, Cairo remains keen to diversify its partners to avoid an inordinate dependency on Beijing. In January 2021, Egypt announced its intent to partner with CMA CGM to develop an additional 1.5-million-TEU container facility at the Alexandria port, reflecting the wider strategic partnership between Egypt and France in Africa.

On the Levantine seaboard, Chinese state-owned Shanghai International Port Group (SIPG), working with Shanghai Zhenhua Port Machinery Company, the world’s leading supplier of heavy loading and logistics equipment, constructed a new, state-of-the-art private port in Israel’s Haifa Bay with a container capacity upwards of 1.86 million TEU. Known as Bay Port, SIPG is slated to operate Israel’s largest container terminal for the next 25 years. With freight rail service to Beit She’an, near the border crossing with Jordan, China could extend the railroad into Jordan, thereby creating multi-modal connectivity with Arab Gulf States. China has also built a new port in Ashdod with additional facilities to create a logistics and high-tech development hub on the eastern Mediterranean. Additionally, Israel is privatizing its state-owned port of Haifa in October and bids from DP World, India’s Adani Ports, and the UK’s DAO Shipping, along with their respective Israeli consortium partners, have been submitted.

Concerned with having an alternative, Levantine trans-shipment hub to preserve its commercial connectivity with countries like Syria and Iraq that would not accept goods shipped via Israel, Beijing set its sights on Lebanon’s northern port of Tripoli. China Harbor Engineering Company (CHEC), which built Israel’s new port in Ashdod, upgraded and expanded Tripoli’s port with advanced Chinese cranes, enabling it to handle 480,000 containers per year. Located about 19 miles (30 km) from the Syrian border, Beijing uses the Tripoli port to service its Syrian reconstruction effort, which prior to the 2019 U.S. withdrawal, was slated to be a $200 million investment that would enable upwards of 150 Chinese companies to operate in Syria under lucrative contracts.

The port of Tripoli has about a third of the capacity the Beirut port, but its capacity could be raised to at least half of Beirut’s with the installation of additional cranes by China. In March 2021, CMA CGM announced that it had acquired all the shares of Gulftainer Lebanon, the operator of the Port of Tripoli container terminal. CMA CGM’s Bosphorus Express (BEX) line operates a direct link from Lebanon’s Tripoli port to Shanghai, Ningbo, and other major Chinese ports. Two weeks prior to CMA CGM’s acquisition of the Tripoli container terminal, the company concluded an agreement with Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba that would see Alibaba’s OneTouch digital platform used for shipment booking and logistics services on the BEX line.

Franco-Turkish maritime cooperation to counter-balance China in the Levant

While a Franco-German partnership in rebuilding Beirut’s port remains a possibility, CMA CGM also has good business reasons of its own to partner with Turkey. Given Turkey’s expanding role in Mediterranean-MENA maritime connectivity, Franco-Turkish cooperation may also be the most strategic way to counter-balance China in the eastern Mediterranean.

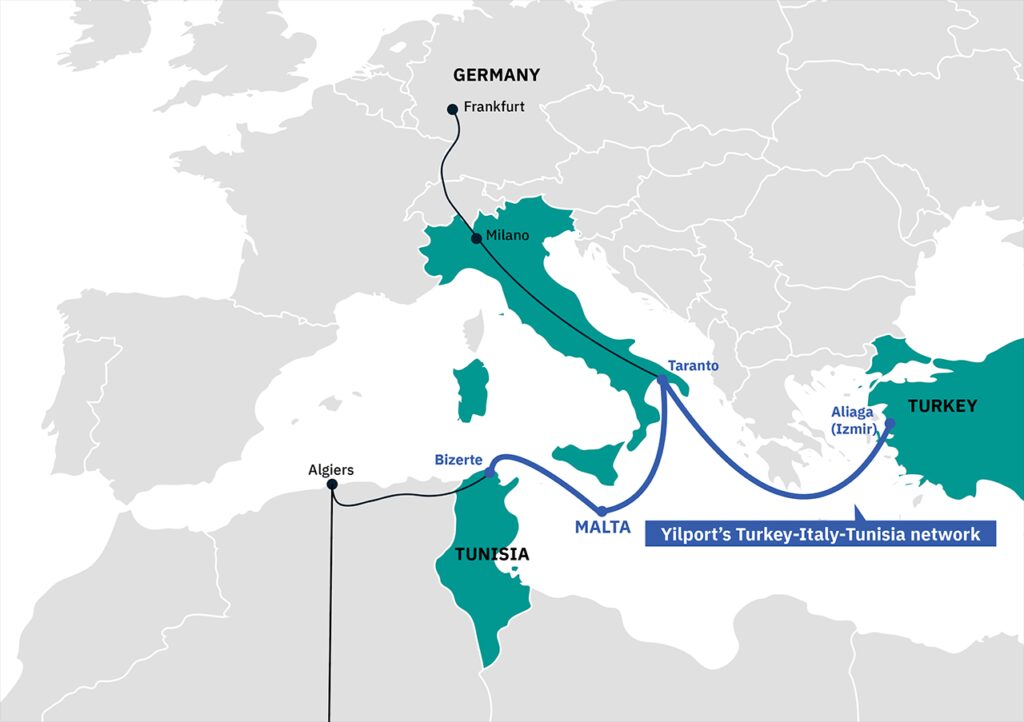

Turkey’s Yilport Holding, a rising terminal operator with global ambitions, established a Turkey-Italy-Tunisia transportation network in 2020 that slices across the center of the Mediterranean, creating an arc of commercial connectivity from the Maghreb to the wider Black Sea. The Turkey-Italy-Tunisia network’s central hub is Italy’s deep-sea port of Taranto, located on the country’s southern tip at the heart of the Mediterranean Sea. The network forms the primary link in an embryonic central Maghreb-based Europe-Africa corridor that utilizes the network’s central node at Taranto, from where it extends southward to Malta’s Freeport Terminal at Marsaxlokk — also owned and operated by Yilport — and then to Tunisia’s port of Bizerte.

Connecting the pieces of Yilport’s Turkey-Italy-Tunisia network is CMA CGM, in which Yilport Chairman Robert Yüksel Yıldırım is a 24% stakeholder. CMA CGM began service to the Taranto port on July 10, 2020, marking the resumption of container traffic at Taranto after a five-year hiatus. With a 23.5% increase in the volume of cargo handled by the port in Q2 2021, Taranto is becoming the geographic crown jewel in CMA CGM’s TURMED service that already links Turkey and Tunisia via Malta. Eight years before Yilport’s Taranto acquisition, the Turkish port operator acquired a 50% stake in Malta’s Freeport Terminal at the Marsaxlokk port on the southern coast of the island around the same time that Yıldırım acquired his share in CMA CGM.

Franco-Turkish cooperation involving Yilport and CMA CGM in rebuilding Beirut’s Port would integrate the maritime architecture of the central and eastern regions of the Mediterranean basin and help offset China’s growing dominance of the commercial sea lanes that connect the MENA region to Europe and Asia. A trilateral partnership between France, Germany, and Turkey within the context of the German proposal for the port’s reconstruction along with major urban renovation of the adjacent neighborhoods of Beirut could also provide a new framework for cooperation in which to reset Europe-Turkey relations.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News