The port of Chabahar—located on the Makran coast of Iran’s Sistan and Baluchistan Province, near to the Gulf of Oman and at the mouth of the Strait of Hormuz—is the only Iranian port with direct access to the Indian Ocean. Thanks to its strategic position and links to north-south transit corridors, it has been termed the “Golden Gate” to landlocked Afghanistan and Central Asia (Strategic Analysis, November 23, 2012). Iran and its northeastern neighbors are not the only actors with a deep interest in the success of Chabahar. Namely, Iran’s “only ocean port” is also a key element of India’s transregional transit and trade strategies.

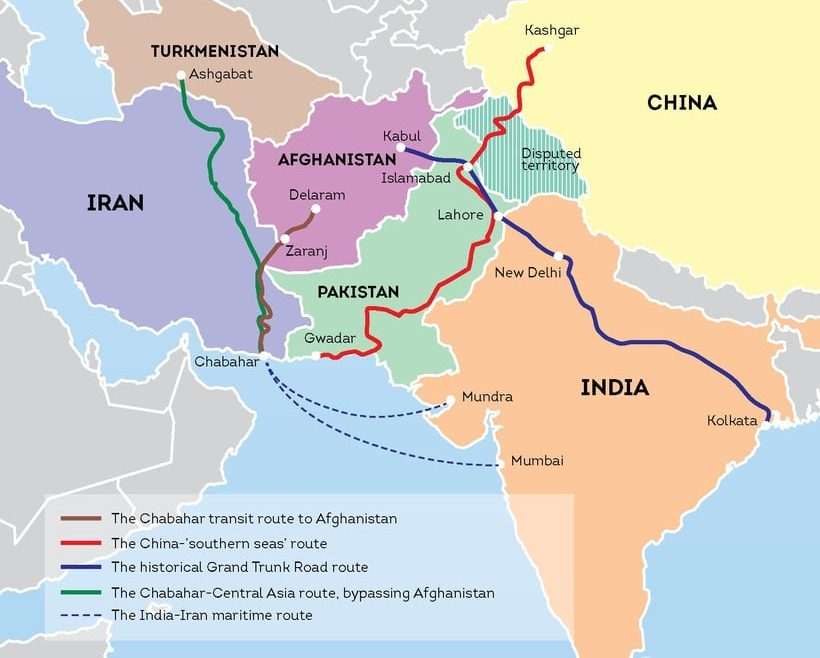

Having witnessed the development of Sino-Pakistani cooperation in the nearby port of Gwadar (Pakistan), India has focused on facilitating growth in the transit capacity at Chabahar in order to boost trade with Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asia while “bypassing” the territory of its regional rivals Pakistan and China. India and Iran first agreed to plans to further develop Shahid Beheshti port (one of the two ports, in addition to Shahid Kalantari, that make up the entire Chabahar port complex) in 2003, but accomplished little toward that goal at the time on account of the international sanctions regime against Iran. A decade later, on May 24, 2016, India signed a historic three-country deal to develop the strategic Iranian port of Chabahar as a crucial node in a “Transit and Transport Corridor” through Afghanistan. By October 2017, India’s first shipment of wheat to Afghanistan was sent through Chabahar. This tripartite agreement not only allowed Indian firms to bypass Pakistan and access global markets to the west but also countered China’s expanding influence in the Indian Ocean region (Hindustan Times, May 24, 2016).

Shortly after the implementation of the Indian-Iranian-Afghan agreement, the Donald Trump administration unilaterally withdrew the United States from the Iran nuclear deal—the so-called Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—on May 18, 2018. Washington then proceeded to re-impose extensive sanctions on the Islamic Republic. But this time, unlike in 2003, the Indians succeeded in persuading the US government to exclude the port of Chabahar from its package of economic penalties. And in December 2018, India took over the port’s operations. Thus, even at the height of the Trump administration’s “policy of maximum pressure” (2018–2020) against Tehran, the port of Chabahar and the Indian-Iranian-Afghan tripartite agreement retained some vital breathing space. By the end of 2020, Iran completed and inaugurated the cross-border Khaf–Herat railway to Afghanistan, which further strengthened the multi-modal (maritime and rail) transit link between these two countries and India.

Following the rise to power of President Shavkat Mirziyoyev in Uzbekistan, Tashkent also started to show interest in accessing the trans-regional transit route via Chabahar. Unlike his predecessor, the late Islam Karimov, Mirziyoyev has been pursuing a policy of “détente” toward Tehran. However, tensions between Iran and Turkmenistan, which have for years hampered overland transit between the Islamic Republic and Central Asia, also motivated Tashkent. Eventually, on December 14, 2020, Uzbekistan, Iran and India held their first (virtual) “trilateral working group” on the Chabahar port. The meeting followed up on decisions taken three days earlier, at an Indian-Uzbekistani virtual summit of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Mirziyoyev (Mea.gov.in, December 14, 2020).

These conditions, which allowed for ever-closer cooperation and agreements among the four regional partners—Iran, India, Afghanistan and Uzbekistan—changed fundamentally after the fall of Ashraf Ghani’s government and the Taliban’s takeover of Kabul, however. Given the close ties between the Taliban and Pakistan, India stands to be a major loser in Afghanistan. And undoubtedly, a major casualty will be the much-vaunted Chabahar port project, which was meant to allow New Delhi an opportunity to sidestep Pakistan and open up a route for Indian goods going to Afghanistan and Central Asia (Scrol.in, August 16, 2021). Shortly after the fall of Kabul, Indian officials declared that “Taliban-ruled Afghanistan will not be part of the India-Iran-Uzbekistan [agreement] to use the Chabahar port in southeastern Iran” (IRNA, August 24).

Without a doubt, the situation in Afghanistan following the takeover of the Taliban will disrupt the Uzbekistani-Afghan-Iranian-Indian quartet. More than 7,200 kilometers of the transit route they had been jointly developing passes through Afghanistan; but no country in the world, including Iran and Uzbekistan, has yet recognized the government formed by the Taliban. The Taliban’s stance on India and Kashmir, which is in line with Pakistan’s, further undermines any prospects for a modus vivendi between Kabul and New Delhi. Under those circumstances, Chabahar has already begun to face delays, which may contribute to India missing its target to boost overall exports by $400 billion in the 2021–2022 calendar year. India’s trade with the entire Central Asia region in addition to Russia, totaled only $16.1 billion in 2020—a mere 2 percent of India’s entire annual volume (Bloomberg, September 17, 2021).

Clearly, the Taliban, along with Pakistan, would prefer to undercut the Chabahar route in favor of the competing China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Within the framework of CPEC, Beijing has already invested heavily in the Pakistani port of Gwadar, located some 100 kilometers to the east of Iran’s border with Pakistan. Therefore, keeping Chabahar economically viable has been a concern for India as it faces competition from China for influence in the region.

In such circumstances, it is likely that Turkmenistan will replace Afghanistan in the quadrilateral Chabahar port usage agreement. But this will require first resolving the Iranian-Turkmenistani disputes over natural gas and restrictions on Iranian trucks crossing the shared border (Iranian Labour News Agency, May 23). Some positive movement on this score has already been observed. On the sidelines of the latest (September 17, 2021) Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit, in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, Iranian president Ibrahim Raisi and his Turkmenistani counterpart, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, notably agreed to resolve the bilateral gas dispute (Tasnim News, September 17). But it remains to be seen how quickly this agreeable rhetoric is turned into an actual policy shift. Such a shift must happen before the multi-modal transit route from India to Central Asia, via Iran’s Chabahar port, can fulfill its long-held economic and geopolitical promises.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News