After more than a decade of subdued consumer price inflation despite gigantic monetary and fiscal stimuli, last year’s surge in consumer prices took most central banks by surprise. First, they tried to dismiss it as “transitory” and caused by pandemic-related supply bottlenecks. Within a few months, when wages started rising strongly, Fed chairman Jerome Powell had to admit that “factors pushing inflation upward will linger well into next year.” He is now claiming that the Fed will take appropriate action to address the inflation problem, but the rhetoric is hardly convincing. Both the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank (ECB) seem to take only baby steps toward ending quantitative easing and raising interest rates, being unwilling to risk a recession in order to tame inflation.

Hiking interest rates will most likely burst the current stock market, real estate, and corporate debt bubbles, revealing the malinvestments stoked by the growth stimuli. The Fed is well aware of this risk because this is exactly what happened in 2019, when financial markets plunged after four interest rate raises in 2018. Instead of continuing the normalization of monetary policy, the Fed lost its nerve and promptly reversed course. That is why many analysts doubt the Fed’s determination to counter the inflation head-on now. Another obstacle to weeding out inflation is the large stock of public debt accumulated since the global financial crisis (GFC) and a worrying relaxation of public spending even in previously frugal economies. Moreover, this trend is backed by growing calls for fiscal laxity among mainstream pundits.

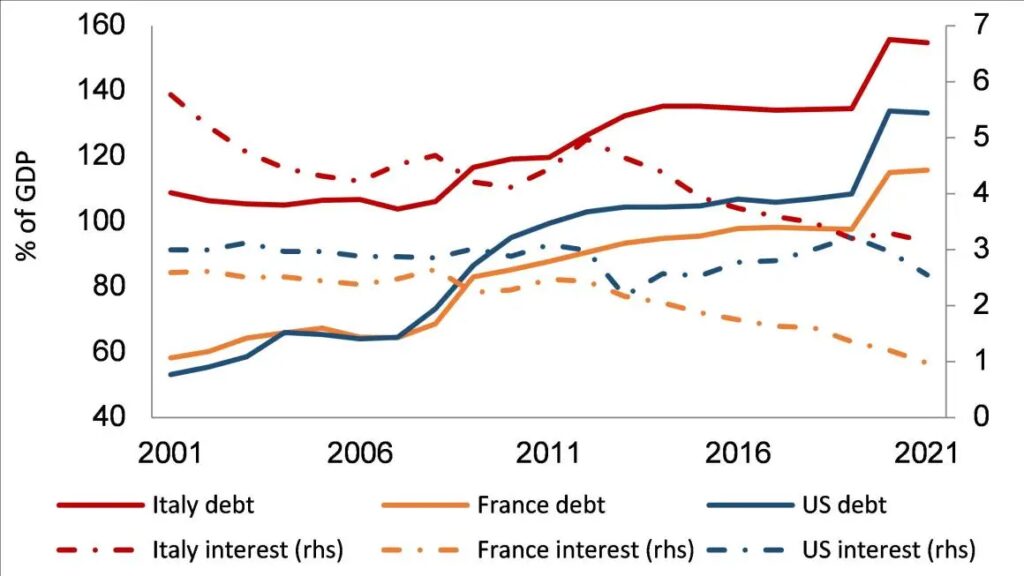

The last two decades witnessed a surge in public debt worldwide. In advanced economies, the public debt burden soared from about 70 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2001 to above 120 percent of GDP in 2021 (see the International Monetary Fund’s [IMF] World Economic Outlook Database). Yet interest payments went down significantly due to record-low interest rates. For example, both France and the US started the new millennium with public debt ratios of less than 60 percent of GDP, which more than doubled in size last year in both countries, to close to 120 percent of GDP in France and above 130 percent of GDP in the US (graph 2). Over the same period, the annual cost of public debt dropped from 2.5 percent to 1 percent of GDP in France and from 3 percent to 2 percent of GDP in the US. Italy’s public debt added about 45 percentage points of GDP, while interest payments halved from about 6 to 3 percent of GDP. A back-of-the-envelope calculation tells us that at the interest rates prevalent before 2001, the annual cost of the current public debt would be about 5.5 percent of GDP higher in Italy and the US and 4 percent of GDP higher in France than it was last year. Moreover, budget deficits in all three countries have swollen to close to or above 10 percent of GDP in 2021 and, according to the IMF, could at best decline to 3–4 percent of GDP in Italy and France and 5 percent of GDP in the US in the aftermath of the pandemic. Facing such a fiscal nightmare, how can anyone expect the Fed or the ECB to move forcefully to normalize interest rates?

Severe Deterioration of Fiscal Positions

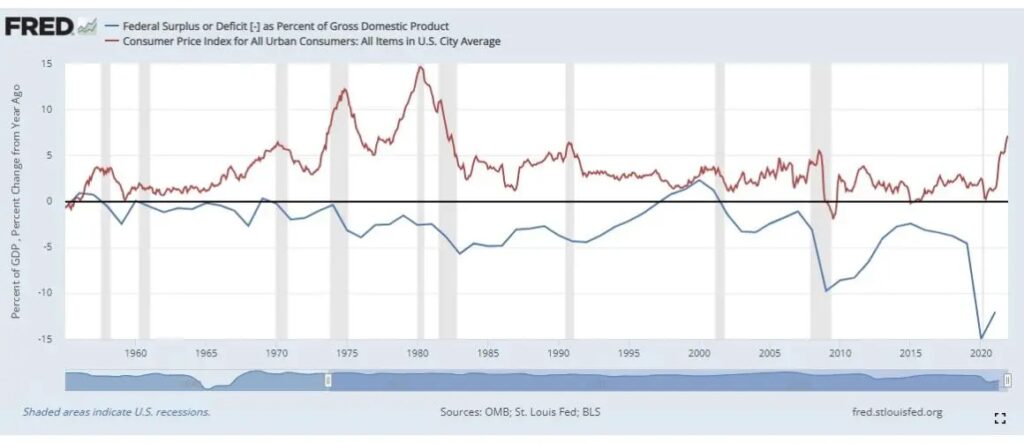

Changes in the fiscal stance have been an important driver of Consumer Price Index inflation in the US during the past seventy years. When budget deficits has widened, annual inflation has pushed close to or above 5 percent, especially after the US went off the gold standard in 1971 (graph 1). The correlation is not one to one, as other factors also contribute to an artificial increase in fiduciary media. But it is almost always the case that when fiscal slippages occur, central banks end up monetizing a larger amount of government debt.

Graph 1: US budget deficit and consumer prices

Graph 2: Public debt and interest payments

Even worse, fiscal profligacy seems to be spreading quicker than the pandemic. If Italy and France have never excelled in fiscal discipline, countries like Australia, Korea, Germany, and the Netherlands used to be well known for their fiscal restraint. That seems to be all gone now. Through recurrent fiscal stimuli, Australia’s public debt surged from a very low level of 10 percent of GDP before the GFC to 62 percent of GDP in 2021 (see the World Economic Outlook Database). Correcting the deficits and debt has now become a serious challenge which is further compounded by a menacing real estate bubble. Since 2017, when President Moon Jae came to power in South Korea, his income-led economic growth strategy, based on boosting consumption and on income redistribution, led to a sizable fiscal expansion. Korea’s long streak of large fiscal surpluses ended abruptly just before the pandemic, and the budget had a deficit of 3 percent of GDP in 2021 (graph 3). This year’s budget spending is projected to grow by another 8 percent in order to expand Korea’s social safety net, subsidize small businesses, and invest in green transition.

Graph 3: General government deficits

Germany and the Netherlands used to be the euro area’s most prominent “frugal” members, running balanced budgets for several years and trying to restrain the fiscal extravagance of other members and the EU common budget. Now both countries have large coalition governments that promised an unprecedented increase in public spending in addition to the expansion seen in the pandemic. The Netherlands’ fiscal position deteriorated from a surplus of 2.5 percent of GDP in 2019 to a deficit of above 6 percent of GDP in 2021 (graph 3). The budget is expected to remain in the red over the next years, as the government plans to spend more on housing, education, childcare, and green transition. Germany ended 2021 with a budget deficit of close to 7 percent of GDP, and its new coalition government has very ambitious green and social agendas. The coalition wants to speed up the abandoning of coal energy by eight years, to 2030, put 15 million electric cars on roads, build 400,000 social housing units and raise the minimum wage to €12 per hour, while still pledging to reinstate the so-called debt brake by 2023 and not raise taxes.

Germany’s inclination toward fiscal loosening is evident not only in higher spending plans, but also in a more dovish stance toward a relaxation of EU’s fiscal rules. The latter were suspended during the pandemic, and heavily indebted countries—such as Italy, France, and Greece—are pushing to relax them in order to accommodate the great need for green investments and to reflect much higher postpandemic debt levels. The EU’s extremely ambitious climate targets are estimated to cost up to 1 percent of GDP in public investment annually during this decade, complicating the challenge of fiscal consolidation even more.1 With less opposition to the relaxation of fiscal rules from the Netherlands and Germany and growing fiscal divergence among euro area members, it is very likely that financial stability and short-term growth considerations will take precedence over fiscal discipline.

Growing Calls to Inflate Debt Away

The same voices asking for large growth stimuli in the aftermath of the GFC are arguing again in pure Keynesian style that austerity is a road to failure, whereas public “investment” will boost growth and ultimately improve fiscal stability by reducing the debt-to-GDP ratios. According to them, Europe should not return to prepandemic fiscal rules, although these were hardly observed even then. The main arguments advanced are the so-called obvious successes of massive deficit spending during the pandemic and the United States’ better growth performance during the Great Recession. But, together with Japan’s “lost decades,” these are precisely very good examples that growth stimuli do not work.

The economic recovery has remained subdued not only in the US, but in all advanced economies that chose to spend their way out of the Great Recession. The levels of public and private debt continued to soar in parallel, while stock exchange and real estate bubbles were reinflated to new highs. With the monetary and fiscal stimuli still in place, the “recovery” is mainly an artificial doping up of GDP, which is likely to burst when the stimulus is withdrawn. The investment and growth strategy advocated by mainstream economists is nothing but a call to inflate debt away via public spending. This is fully oblivious to the disastrous effects that an acceleration of money printing would have—exacerbating capital erosion and distortions in the structure of production.

Some inflation proponents also try to use econometric modeling to show that monetary policy has not been expansionary enough so far, being constrained by the zero lower bound. In their view, quantitative easing can help reach inflation targets and reduce debt costs so that fiscal policy can intervene more aggressively to support growth and eventually stabilize the fiscal position. If this is true, why have debt levels not stabilized already, after decades of generous fiscal stimuli? And what explains the asset bubbles that have mushroomed during the last two decades if monetary policy has been too tight? In reality, the supposed “virtuous” synergy between monetary and fiscal relaxation can only end in a senseless spiral of debt and inflation out of control. The historical examples of Argentina and Germany illustrate very well the risks of debt monetization slipping into hyperinflation and economic collapse. All the mainstream proinflation propaganda is definitely not a good sign that governments are about to put inflationary policies on hold any time soon.

Expectations for Higher Inflation

Surveys show that people are starting to realize that inflation is likely to increase further rather than fade away. This is gradually fueling requests for higher wages and a willingness to part more quickly with cash. As argued in a recent article, once inflation expectations become entrenched, the central bank’s space to control inflation and use it to inflate debt away will significantly narrow. Thorsten Polleit brings good arguments that the Fed may only want marginally higher inflation, in a range of 4 to 6 percent per year, without letting it get out of control. But given the toxic interaction with already very high debt levels and rising inflation expectations, the central banks’ plans could easily be derailed.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News