The challenge of developing export strategies for the offshore natural gas resources concentrated in the Eastern Mediterranean predates the Russo-Ukrainian war, which exploded in full fury in late February of last year. Yet over the course of 2022, Europe’s intensifying energy crisis created a new and more immediate incentive to solve those export challenges, despite a great deal of work still to be done.

New discoveries

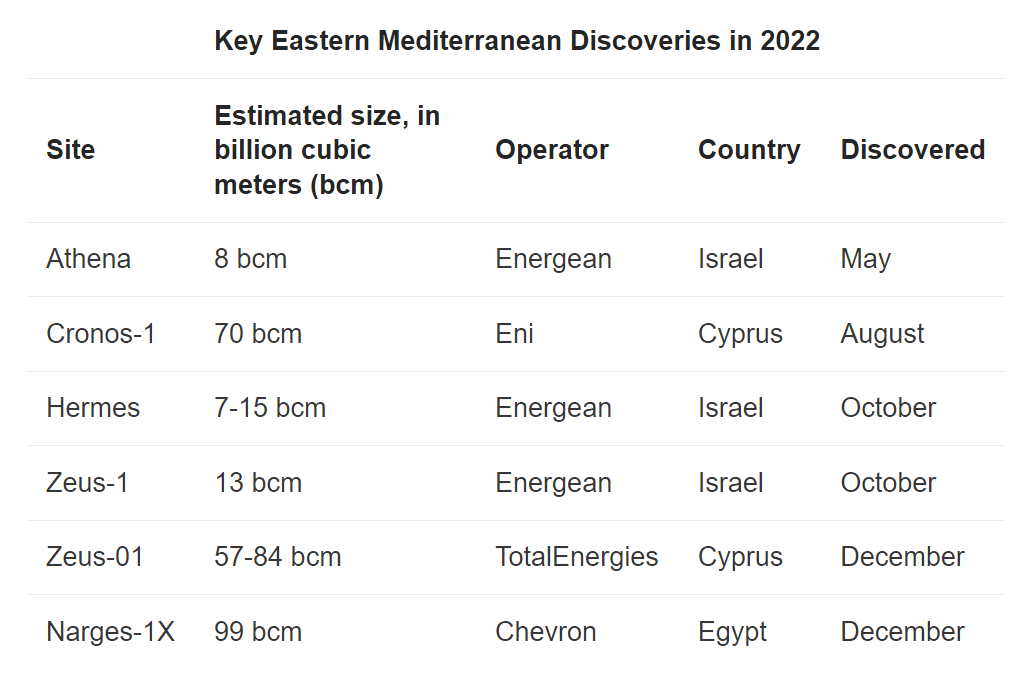

The year 2022 saw a succession of new gas discoveries in Israel, Cyprus, and Egypt. None of the headline numbers yielded by these discoveries would have attracted attention on par with that of the region’s biggest finds, such as Egypt’s Zohr or Israel’s Leviathan field, but new reserves in proximity to existing production infrastructure will support exports from the Eastern Mediterranean. Notably, discoveries in Cyprus further enhance the island country’s prospects of joining its neighbors and finally becoming a gas exporter, even if the optimal route for exports remains unclear or cannot be pursued.

While no individual find was particularly large, collectively they will support continued development and production in the region once connected to the existing infrastructure. At the end of 2022, a new discovery in Cypriot waters again raised questions about export prospects for its yet-undeveloped reserves. Although the possibility of piping gas to the European mainland or constructing new liquefaction capacity on the island has been raised in the past, current options appear most likely to involve a floating liquefied natural gas facility (FLNG), also under consideration in Israel, or a tie back to Egyptian LNG plants.

New projects greenlit, export questions remain

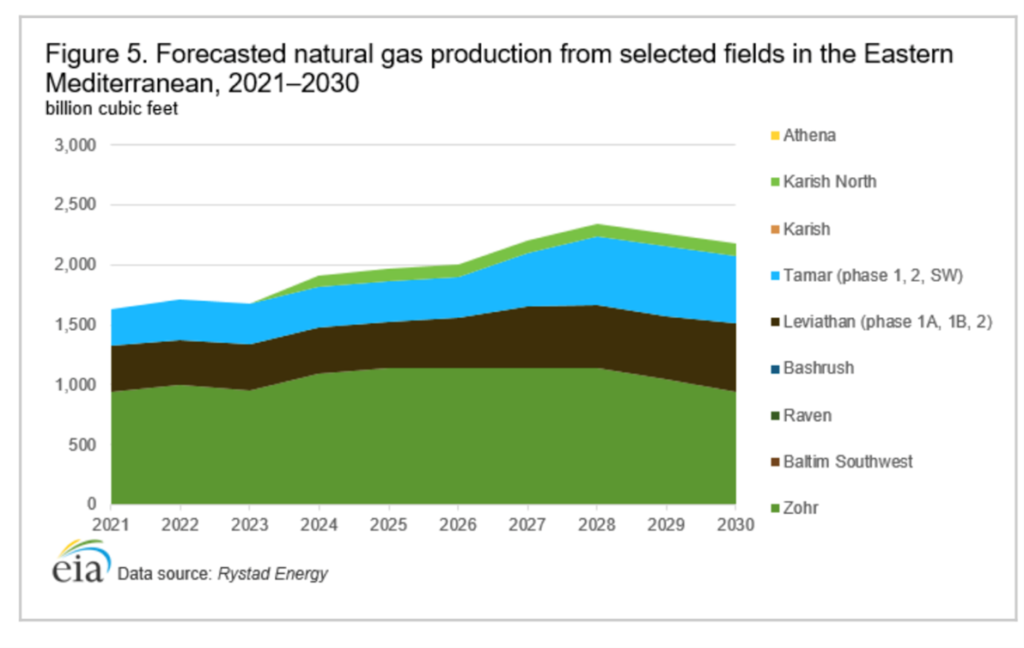

For all the new interest, diplomatic progress, and commercial activity that took place during 2022, alternative export pathways from Egypt’s two liquefaction plants at Idku and Damietta failed to materialize. Ongoing debottlenecking work in Israel and plans for a new onshore pipeline will enable higher volumes to flow to Egypt, but these projects do little to advance new phases of Leviathan development or new resources from Cyprus, and this will remain a critical area to achieve progress in 2023.

While much has been made of new discoveries, planned capacity expansions to Israel’s key Leviathan and Tamar fields were also greenlit in 2022. Since Israel is not in need of more gas and represents a relatively small demand center to begin with, this is a positive development for exports. Indeed, the region’s complicated political and regulatory landscape has hindered international oil companies’ (IOCs) ability to firm up export strategies, which has in turn held back final investment decisions at existing fields. The upstream work that was approved for the Leviathan and Tamar fields, therefore, will result in a significant expansion of Israel’s gas production capacity over the next several years, in addition to upgrading infrastructure that may increase the viability of developing newer, smaller discoveries.

Diplomatic progress

The late-October agreement that settled a maritime dispute between Israel and Lebanon was an urgent matter due to the planned startup of production at Israel’s Karish field, which straddles its northern sea boundary with Lebanon. Notably, the floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) offshore production vessel chartered/owned by the Greek firm Energean was directly threatened by Lebanese Hezbollah, signifying the sensitive nature of offshore gas extraction in a region where Israel and Lebanon’s maritime demarcation dispute is far from the only one.

The agreement will allow offshore exploration in Lebanon to resume, with a consortium led by TotalEnergies planning to drill in the first quarter of this year. Importantly, the deal also reduces geopolitical risks to further development in the region. Its market impact is less significant, for now, but the resolution of a major dispute between two countries that do not have formal diplomatic ties is a sure sign of regional progress. Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s resurgent prime minister, has criticized the agreement in the past but currently looks unlikely to reverse it. Doing so would inject new volatility into Israel’s upstream sector just as it is holding a fourth offshore bid round (OBR4) that seeks to attract new investors. Looking ahead, it is likely that more such diplomatic progress will be necessary to unlock some of the Eastern Mediterranean’s most optimal export routes, a prospect for which there is little guarantee.

What to watch in 2023

Bid rounds in Israel and Egypt

Israel’s OBR4 was officially launched at the end of 2022. The development was the result of a policy U-turn on the part of Israel’s previous government, as former Energy Minister Karine Elharrar had announced that plans for the bid round would be shelved in late 2021, only to reverse this stance after Russia’s large-scale re-invasion of Ukraine. Israel’s new government under Netanyahu is highly unlikely to alter these plans, and may instead relax export quotas. OBR4 will provide a range of insights relating to IOC interest in the Israeli upstream, which did not attract a supermajor like Chevron until recently, when the firm acquired U.S.-based Noble Energy in 2020.

In nearby Egypt, another bid round was launched at the very end of 2022, with 12 blocks in the Mediterranean and Nile Delta areas on offer. The round is set to remain open until April, and as with Israel, its results will gauge IOC interest in Egypt as activity picks up in the Eastern Mediterranean once again. This new activity has also spurred IOC interest in existing discoveries previously deemed uneconomic.

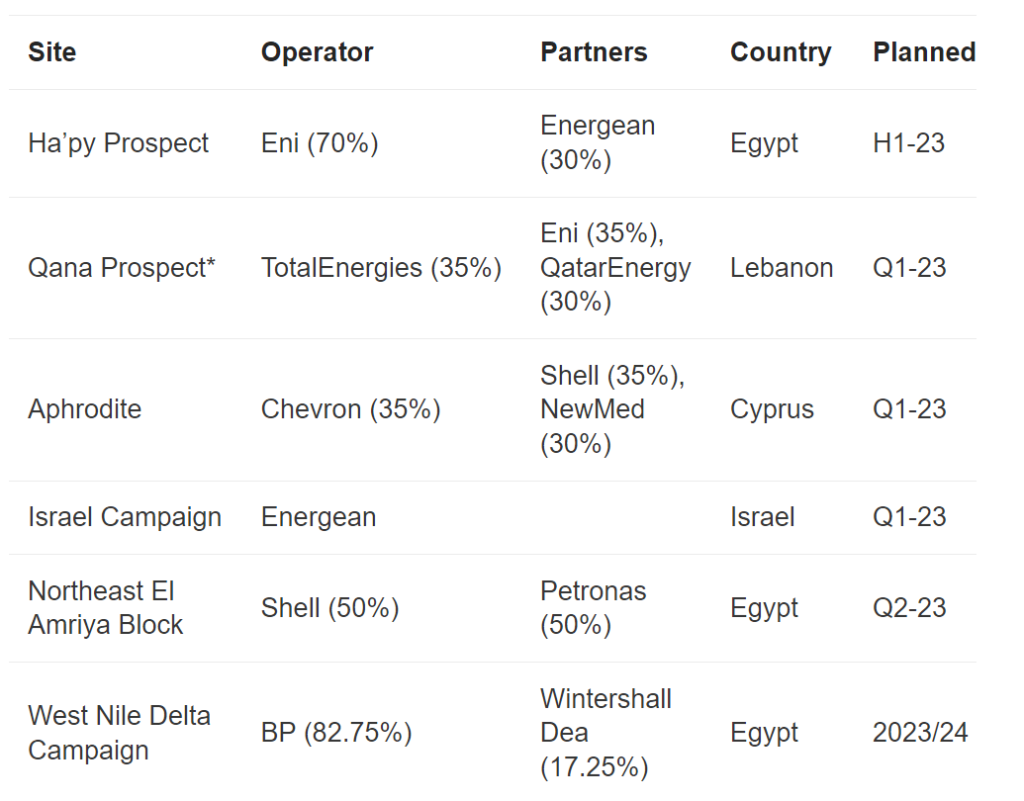

More drilling

Regional operators plan to continue drilling into 2023, with discoveries from 2022 likely generating renewed attention. Continued drilling will also be critical to making progress on higher export volumes, which will require enough gas to ensure that the Eastern Mediterranean’s regional market, however small, remains well supplied. Key to accomplishing this will be new supply in Egypt, by far the largest gas market in the region. To that end, new discoveries and plans for drilling in Egypt’s Mediterranean waters will likely continue to support these needs, though development timeframes will of course remain a critical variable. Yet as piped gas from Israel continues to support LNG exports from Egypt, new supply will ensure that imported gas does not need to be redirected to satisfy domestic demand.

Key Eastern Mediterranean Drilling Planned for 2023

Source: Energy Intelligence

Potential new export routes

For the last several years, conventional wisdom surrounding LNG exports from the region favored Egyptian liquefaction capacity as the most viable route. Though other, highly ambitious plans have been floated, project economics are a key consideration in this context, not to mention difficulties presented by the region’s various ongoing maritime boundary disputes. Connecting new fields to Egyptian or Israeli infrastructure that would then direct gas to Idku or Damietta still appears to be a favored option for IOCs, but there is enough of a possibility that new export routes will also emerge over a longer time horizon.

The potential for options remains unclear even after several years of speculation, however; and it is possible that the results of drilling campaigns planned for 2023 will further alter the dynamics of this situation. Israeli concerns over coastal development make it highly unlikely that new liquefaction capacity will be built there, though Chevron has consistently hinted at FLNG as a distinct export possibility. Cyprus, whose sector is ever-complicated by Turkish and Turkish-Cypriot claims, has alluded to the potential construction of new liquefaction capacity if its reserves are significantly proven-up. Yet Cyprus’ Energy Minister Natasa Pilides recently acknowledged that linking Cypriot discoveries to Egyptian LNG plants does appear most likely. It is entirely possible that 2023 will pass with some of these questions left unanswered, but activity planned for this year has the potential to provide more definitive signals on the direction in which these developments may lead.

Geopolitical constraints will loom large

While the Israeli-Lebanese maritime agreement removes significant risks to gas production in the region so long as it remains in place, other diplomatic issues still stand in the way of new resource development. Key to this trajectory will be Turkey’s diplomatic posture in 2023, along with its attempts to achieve rapprochement with several states in the region, namely Israel. Notably, Turkish maritime claims as well as those of the self-proclaimed (and Ankara-backed) Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus are among the main obstacles to designs for the Eastern Mediterranean (EastMed) Pipeline, which for now appears highly improbable. Though diplomats have voiced support for the project in the wake of the Ukraine crisis, none of the region’s IOCs have offered to back the idea, nor has there been any major push from regional bodies like the East Mediterranean Gas Forum to advance the plan. Though cost is a strong consideration, the political shifts needed to make the project viable are highly unlikely to be achieved in the near term.

The lack of a final agreement between Israel and Cyprus concerning the status of the Aphrodite/Yishai field is less of an impediment to progress, but it does limit potential export routes for undeveloped Cypriot reserves. Key to this issue is the potential for linking the Aphrodite discovery with Israel’s Leviathan, both of which are operated by Chevron. However, the more likely export route for the moment appears to be a linkage to the Egyptian LNG terminal at Idku, which is operated by Shell, another Aphrodite partner. A linkage from Cypriot to Egyptian assets may be more viable from a diplomatic standpoint, as any Israeli agreement with Cyprus holds the potential to antagonize Turkey, with which Israel is currently in a state of rapprochement.

In Israel, notable entries like the United Arab Emirates’ Mubadala Energy have somewhat overshadowed the fact that the Israeli state’s most recent election was its fifth in three years. Domestic political volatility presents very real operational risks, to say nothing of tensions with neighboring states that have a precedent of disrupting gas extraction. Should hawkishness in the Netanyahu coalition (or events outside Israeli control) lead to a flare-up in violence between Israel and any of its neighbors, a supply disruption is a distinct possibility. The newfound attention given to Israeli gas assets in light of Europe’s energy crisis is unlikely to be lost on Israel’s detractors. As such, the range of positive developments Israel enjoyed in its gas sector during 2022 far from guarantee that this year will go as smoothly.

More Gulf investment?

Gulf state-owned hydrocarbon companies also solidified their presence in the region during 2022, with QatarEnergy farming into its third exploration block in Egypt and replacing Novatek in the TotalEnergies/Eni consortium in Lebanon. UAE-based Mubadala Energy is keen to promote the fact that its hydrocarbon production portfolio, which has reached an equivalent of 500,000 barrels per day, consists of 70% gas production, and its 22% stake in the Tamar field makes it the most substantial Gulf player in the region. Moves to establish an international arm of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) hardly guarantee an expanded Emirati presence in Israel’s upstream, but such an entry would no longer lack precedent.

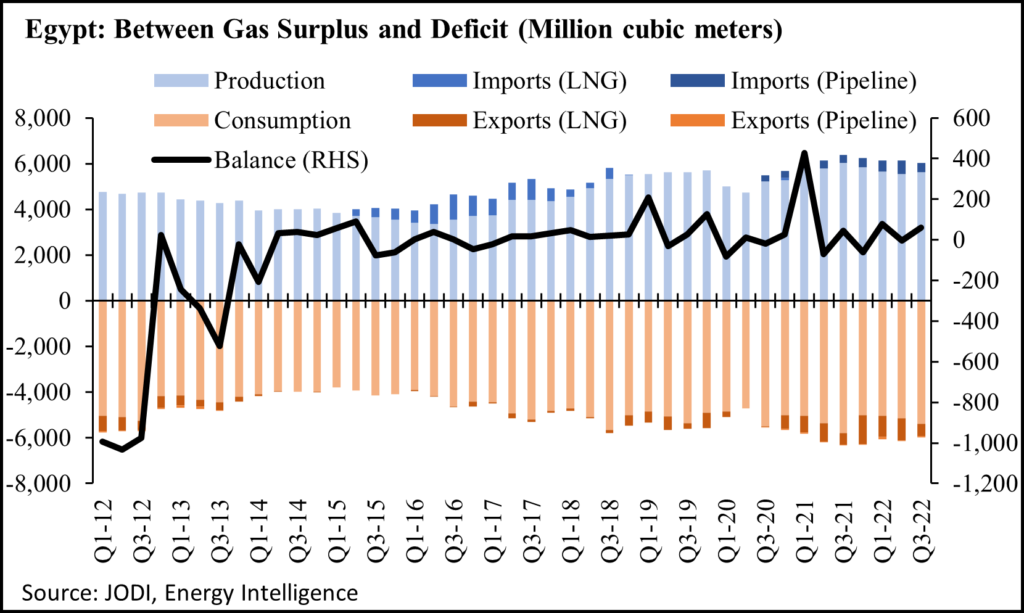

Regional gas demand will remain a factor

A key factor to maintaining exports is gas demand in the region itself, the overwhelming majority of which is accounted for by Egypt. Gas consumption in the country reached 61.9 bcm in 2021, dwarfing 11.7 bcm in Israeli demand the same year. LNG exports have helped prevent Cairo’s dire fiscal position from worsening, which was likely the motivation for introducing demand management efforts last year that included reductions in lighting and air conditioning use at key government and commercial facilities, in addition to increasing the domestic use of dirtier, more expensive liquid fuels in its power mix.

This development is itself a departure from precedent, since serving domestic demand has previously been more of a priority for Cairo than maintaining exports. Over the next several years, new discoveries will increase long-term incentives to develop more Egyptian supply, and growing use of renewables will also provide relief to strained gas supplies. However, with its demand for gas still growing and renewables making up just 10% of its power mix, Cairo will likely walk a fine line between running a gas surplus or deficit for at least another few years.

Beyond 2023

Sooner or later, the war in Ukraine will end. Yet Europe will still have a strong need for additional gas supplies, as it is highly unlikely that imports from Russia will resume in the foreseeable future, if ever. While the rush to secure new supply has seen considerable progress in the space of just one year, the diplomatic and commercial work that will result in steady LNG cargoes heading to Europe from the Eastern Mediterranean will not be completed in 2023. Progress will remain vulnerable to unforeseen events and exogenous shocks that impact regional states, but in many ways these factors represent business as usual for a region that is no stranger to volatility. Still, a more integrated, gas producing “East Med” region finally looks to be on the horizon.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News