In Syria’s border regions, changes in demographics, economics, and security mean that an inter-Syrian peace process will require consensus among main regional powers that Syria must remain united, that no one side can be victorious, and that perennial instability threatens the region.

Summary

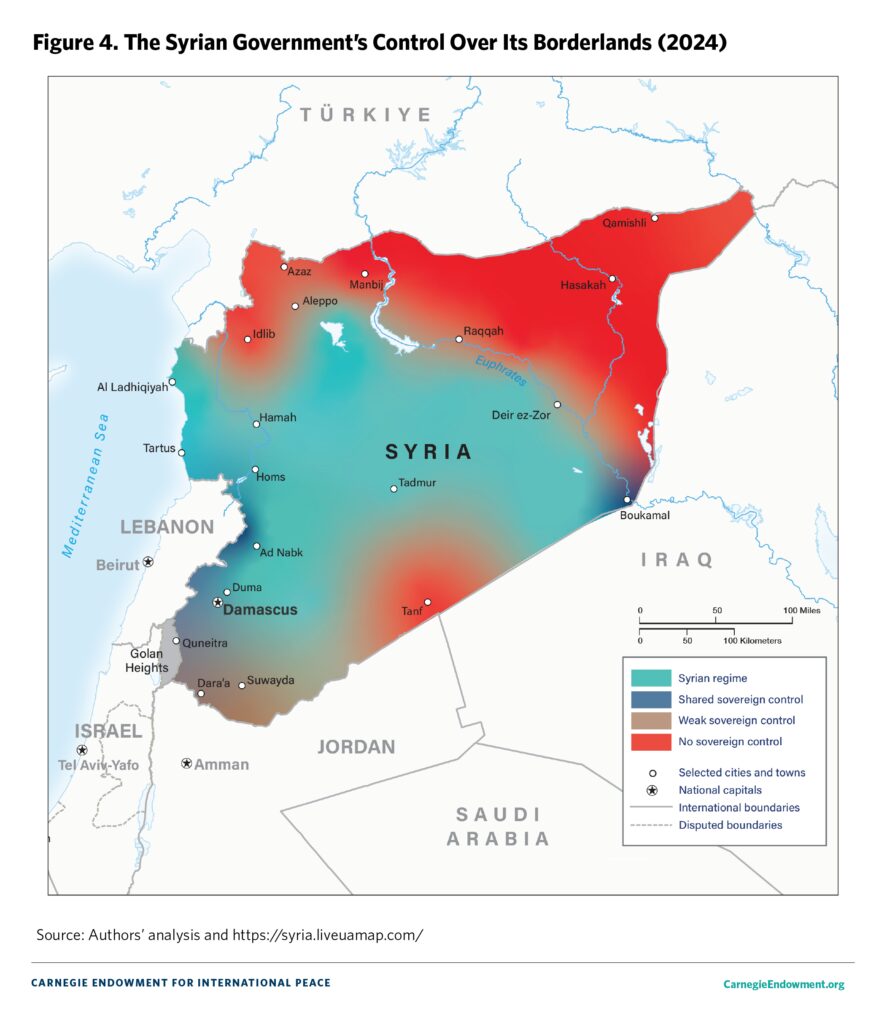

Syria’s central authorities have lost sovereignty over their border regions, which are being contested by local, regional, and international actors. This will not soon change, making the Syrian crisis almost irresolvable, with potential risks for all sides as parts of Syria potentially face internal implosion, impacting outside actors. Given that no one side can win an absolute victory, a broad solution for Syria lies in bringing its dynamics back to a national framework.

Key Themes

Syria’s conflict has transformed the country’s border regions. Türkiye has influence over much of the northern border; Iran has significant influence over the border with Iraq and Jordan, and indirectly, through Hezbollah, over the border with Lebanon; and the United States has outposts of influence along Syria’s northeastern and eastern borders, down to Tanf.

The border regions differ from each other, but all have become autonomous zones through the interactions between local actors and regional states, including allies of Syria’s government. Each has its own economy, security, and even ideology—forming de facto cantons outside Damascus’s control.

Demographics, cross-border economic relations, and security have emerged as the main drivers of this situation. The interaction of these factors continues to shape sociopolitical patterns across Syria’s borderlands.Findings/Recommendations

The Syrian war has radically reshaped Syria’s demographics. Some 14 million people have left their homes or been forced out, while a new generation has been born into a divided Syrian reality.

The Syrian conflict has reshaped cross-border economic networks, while giving rise to new economic centers and actors outside Syrian government control.

In the last decade or so, Syria has seen the establishment of parallel security orders—Turkish, Iranian, and American—each within specific zones of operation or influence.

Because violence persists mainly in border areas, over which regional and international actors have sway, any resolution of the Syrian crisis must address this reality and revive a national Syrian framework.

Syria’s internationally recognized borders remain intact, paradoxically. The struggle for Syria and the instability this has generated have reinforced a belief among regional countries that these borders must be preserved.

An agreement to restore national authority in an inter-Syrian process would rest on a consensus among main regional powers that Syria must remain united, that no one side can be victorious, and that perennial instability threatens the region.

Wagering on the rationality of regional and international actors may be impossible, but containing Syria’s dynamics indefinitely, without a resolution, may lead to internal implosions that ultimately have regional ramifications.Introduction

The conflict in Syria has transformed the country’s border regions. Damascus has lost control over most of these regions, while it retains only hypothetical control over others in which allies of President Bashar al-Assad’s regime dominate. Control over borders has always been a central dimension of the power of the Baathist state and is a barometer of any state’s sovereignty in general. Yet today, the control of Syria’s central government over the country’s border areas is being contested by local, regional, and international actors, leading to a proliferation of political authorities, or centers, with influence in these areas.

Türkiye has sway over much of the northern Syrian border. Iran has significant influence over the eastern border region with Iraq and, indirectly through its Lebanese ally Hezbollah, over the western border with Lebanon. The United States, in turn, has established military outposts along Syria’s northeastern and eastern borders, down to Tanf near Jordan. The border regions differ from one another, but all have one characteristic in common: they have become largely autonomous zones, with their own economy, security, and even ideology, having been transformed into de facto cantons outside the control of Damascus.

A major consequence of this reality is that it has put in motion a long-term trend in which Damascus will not soon restore Syrian state sovereignty over most Syrian border areas. On the contrary, in the coming years the dynamics in the borderlands will continue to be defined principally by the local, regional, and international actors and the interactions among them.

Along all of these borders, however, multiple factors are affecting outcomes, and these can broadly be reduced to three: demographics, or the matter of refugees; markets, or what can more broadly be called cross-border economic relations; and security. Given the fact that Damascus is unable to soon restore full control over its border areas, any resolution of the Syrian crisis will necessitate moving away from the political initiatives proposed for, or implemented in, Syria until now—whether the United Nations plan for Syria embodied in Security Council Resolution 2254 or the more limited accords over specific geographical areas reached through the Astana process, which included Russia, Türkiye, and Iran.

It is exceedingly difficult today to conceive of a detailed plan to bring the crisis in Syria to an end. However, the situation that prevails, in which regional and international actors continue to pursue their conflicts on Syrian territory, is unlikely to bring about absolute victory by one side. On the contrary, these conflicts make it all the more probable that the Syrian state will continue to disintegrate, so that Syria will remain a major source of regional instability, with potential risks for all those involved in the country. At the same time, perpetuation of the current status quo heightens the risk of internal implosions in regions controlled by the Syrian government, as well as those under the authority of its foes. This risks undermining the equilibrium that exists between outside actors in Syria. In light of this, a broad consensus is needed to bring the dynamics in Syria back to a national Syrian-Syrian framework, within which the contending parties can reach a settlement stabilizing the situation in the country.

The Dynamics in Syria’s Border Regions After 2011

The Syrian uprising began in March 2011 with largely nonviolent protests against the regime of President Bashar al-Assad, before expanding into a full-fledged civil war in mid-2012.1 As the death toll rose, the fighting spread to major cities and regions throughout Syria, soon becoming a focal point for regional rivalries and ambitions. Although pockets of armed resistance to government forces emerged across the country, it was in the borderlands that the regime was at its weakest and the rebels strongest. In those areas, rebels were unlikely to survive without the critical cross-border support they received from foreign countries. More than twelve years later, the Syrian conflict remains very much centered around borders.

As Syria’s uprising became increasingly violent, government forces lost one border area after the other or abandoned them in favor of defending critical urban areas and logistical infrastructure. In those borderlands, local actors with strong ties to regional powers emerged to fill the void left by the state. Since 2012, the control map of Syria has changed countless times. The merciless conditions of war have filtered out weaker local groups, with only the fittest surviving, especially those that have benefited from sustained foreign protection. These groups continue to challenge the regime’s domination and the state’s sovereignty. They include not only opposition groups but also the Assad regime’s allies, who have supplanted Damascus’s authority in many border regions—especially those shared with Lebanon and Iraq.

Developments Along the Northern and Northeastern Borders

Syrian government forces were most vulnerable along the 900-kilometer northern border with Türkiye. By the end of 2012, the regime had almost no control over this region. In the northwest, the regime lost the hinterland and borderlands of Aleppo and Idlib Governorates to emerging local opposition civilian bodies, which replaced Syrian state institutions in providing aid and services.2 On the military front, dozens of local armed groups of many persuasions appeared in the region, ranging from criminal gangs to what are considered “moderates,” such as the Free Syrian Army, to Kurdish groups claiming to be pursuing autonomy in the Syrian state to Salafi jihadists such as Jabhat al-Nusra and, since 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS).3 Jabhat al-Nusra evolved into Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, which today dominates Idlib Governorate. This mosaic was present throughout the northwest, with the exception of Afrin, which was controlled by the People’s Protection Units (YPG), the armed wing of the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD).

In the north and northeast, the Syrian army and security forces withdrew from predominantly Kurdish areas in summer 2012, allowing the PYD to fill the vacuum. The PYD is an offshoot of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), a Türkiye-based Kurdish group that Ankara considers to be a terrorist organization.4 Over the years, the PYD has dominated large parts of Syria, forming a de facto autonomous region known as the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, or AANES.5 This transformation took place much to the Assad regime’s and Türkiye’s displeasure. AANES is protected by the YPG-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), and it has forged an alliance with the United States in light of their joint collaboration in combating and defeating ISIS.6

Borders, border security, and cross-border aid have had highly consequential impacts on Syria’s northern borderlands. The Syria-Türkiye border became a crucial conduit for channeling military and financial aid to Syria’s “moderate” rebels.7 For Salafi jihadi fighters it served as a passage into Syria, where many radical groups were forming, as it did for Kurdish fighters who crossed into Syria from Türkiye to join the PYD/YPG.8 Initially convinced that Assad’s days were numbered, Ankara did not feel threatened by the Kurdish insurgency. However, when the Syrian president showed unexpected resiliency, Türkiye suddenly found itself threatened by its archenemy in Syria, as Kurdish leaders laid the groundwork for an entity they ruled through PKK-trained and -linked cadres.9

The year 2016 was one of the most significant in Syria’s conflict, profoundly changing the face of the country’s north. A combination of factors brought this about, including the fact that the Russian intervention in September 2015 had altered the military balance, forcing key supporters of the Syrian rebels to renounce their goal of regime change in Damascus. Ankara doubled down in preventing Kurdish dominance on its border. While the United States, in alliance with the Kurds, fought to eliminate ISIS, the Assad regime achieved major victories, the most important one being the retaking of Aleppo in December 2016. Within a few years, the number of local and outside actors involved in the Syrian conflict decreased dramatically.

In the north and northwest, where Türkiye intervened militarily and expanded its control through a series of military operations between 2016 and 2019, two local actors remained on the ground: Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, with its Salvation Government in Idlib Governorate, and loosely connected local councils under the opposition’s interim government, operating alongside the Syrian National Army, which had consolidated the remnants of the Free Syrian Army.10 In the northeast, the Kurdish autonomous administration survived in large part thanks to the U.S. presence. All these local actors challenged the Assad regime, limited its reach, and benefited from Turkish or U.S. protection, a situation that persists to this day.

The Situation in Southern Syria

The evolution of the conflict in the south, made up of Daraa, Quneitra, and Suwayda Governorates, at first followed similar lines as the north. Local civilian bodies replaced the state while dozens of armed groups fought government forces and pushed them away from the border. Here, the influence of Salafi jihadi groups was more limited and weaker than in the north.11 The main player was the so-called Southern Front, a constellation of forty-nine armed groups based mainly in Daraa Governorate that received aid from an operations room based in Jordan in which several Arab and Western countries participated.12 Unlike Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham in the north, no one group came to dominate the south. Yet foreign support dwindled and eventually stopped in 2017, when U.S. priorities in Syria shifted away from toppling the Assad regime.13

The new situation allowed government forces to recapture the region in summer 2018, thanks to a deal brokered by Russia. The deal removed U.S., Israeli, and Arab opposition to the Syrian military’s return by accepting the condition that Iran and its allies not deploy to the south.14 However, in the past five years the regime has failed to impose its writ, while Russia, because of its involvement in Ukraine, has seen its influence wane.15 Today, the situation is very fluid. Though the government never lost Suwayda Governorate, its authority is now being contested there.16 Government forces also face challenges in Daraa Governorate, while Iran and its allies have expanded their influence into Quneitra Governorate.17

Syria’s Eastern and Western Border Regions After 2011

The evolution of Syria’s eastern and western borderlands is somewhat different than the situation along the northern and southern borders, as both Lebanon and Iraq are countries under Iranian influence and host nonstate actors supportive of the Syrian regime.

In the first years of the Syrian conflict, military assistance to opposition groups inside Syria entered from Lebanon.18 For instance, the supply lines to the city of Homs ran through the Syrian border town of Tal Kalakh.19 Similarly, the supply lines to Qusayr also extended from Lebanon.20 Starting from April 2013, Syrian government forces and Hezbollah launched several offensives in the border regions, as a result of which they captured Qusayr and Tal Kalakh, before taking control of the entirety of the Qalamoun Mountains in the period leading up to August 2017, when the last rebel factions left the area as part of a ceasefire deal agreed with Hezbollah.21 During the previous month, in July 2017, Hezbollah had organized an operation to clear Salafi jihadi groups from the area around the Lebanese town of Arsal.22 The party’s success on both sides of the border helped it to consolidate its control over that portion of the Syria-Lebanon border. Qusayr has since become a Hezbollah stronghold.

The conflict along Syria’s border with Iraq shares many of the characteristics described earlier. As Syria’s second-longest border, stretching for some 600 kilometers, the Iraqi border has served as a resource for various types of actors. As in other parts of Syria, by the end of 2013 Syrian government forces had withdrawn from much of the border area.

In the northeast, especially in Syria’s Hasakeh Governorate, those who filled the vacuum were the Kurds, principally the YPG, while along the eastern border different rebel groups took control of parts of Deir al-Zor Governorate. Toward the end of 2012, the Assad regime had lost the strategic Qaim-Boukamal Crossing with Iraq.23 Within a year, it had almost no control over the Euphrates riverbank in Deir al-Zor and had lost all major oil fields north of the river.24 Once the regime was out of the picture, rebel groups fought among themselves, especially for control over economic resources. Ultimately, after bloody battles, ISIS triumphed over all these groups in 2014 and declared an Islamic Caliphate in June, before erasing the border between the territories it controlled in Syria and Iraq, which stretched from parts of Aleppo Governorate all the way to Mosul in Iraq.25

The emergence of ISIS led to the mobilization of local, regional, and international forces to combat the group in Syria and Iraq beginning in 2016. Syria, Iraq, Russia, Iran-backed militias, and a coalition of Western and Arab countries led by the United States waged war against ISIS simultaneously. Following the defeat of ISIS in 2019, Iraqi government forces redeployed to some border points.26 As zones of ISIS control shrank, the SDF filled the void in northeastern Syria, north of the Euphrates River. In the context of the war against ISIS, American forces also boosted their presence in Tanf, near the intersection of the Syrian, Iraqi, and Jordanian borders, where they trained a proxy force to fight ISIS.27 The remaining parts of Deir al-Zor came under Syrian army control, backed by pro-Iran militias, who replaced ISIS along the southern stretches of the Euphrates.

On the Iraqi side, a powerful new actor gained influence in the border area after the defeat of ISIS. This was the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), particularly factions allied with Iran operating under the PMF umbrella.28 Among them was the Taffuf Brigade, an armed group that was initially close to the Shia religious authority in Najaf, led by Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, before it gradually aligned itself more closely with Iran. Additionally, Kataib Hezbollah deployed fighters specifically in the Qaim and Akashat areas, where Qaim-Boukamal Crossing is located.29 These groups were part of the Iran-backed Axis of Resistance, which is focused on confronting U.S. and Israeli influence in the Middle East.

The PMF factions also spread to the northern parts of the Syria-Iraq border, particularly in the Sinjar area, where there was intense competition for control between the autonomous Kurdistan Region in Iraq and the Baghdad government.30 Whereas the YPG dominate the Syrian side of the northern section of the border, on the Iraqi side several groups are present. These include Yazidi factions supported by the PKK, which deployed fighters and helped create local militias in Sinjar, as well as Sunni tribal factions affiliated with the PMF.31

This complex map reflects the influence of external actors. Most notable among them is Iran. The Iranians, through the deployment of their allies on both sides of the Syria-Iraq border, not only seek to guarantee territorial continuity between Iran and Lebanon, arm and support their Lebanese ally Hezbollah, and create means of pressure on U.S. forces in the border area but also to place allies in positions where they can attack Israel and support the Assad regime in Syria. The United States, in turn, has established military bases near the Syria-Iraq border, giving them political and military leverage in Syria, leaving a force in place to combat ISIS cells and allowing them to monitor the activities of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and its allies. Finally, Türkiye has also increased its activities in the borderlands, as it has intervened militarily against PKK strongholds in Syria and Iraq to prevent the emergence of a Kurdish political entity allied with the PKK in these territories.32

More broadly, after more than a decade of war, Syria’s border areas have a plethora of local actors enjoying foreign support or protection for their survival. This, in turn, has ensured that the Syrian state’s sovereignty and control over these areas are now shared, weak, or entirely absent. This is as much a result of the presence of the Assad regime’s allies as of its enemies. However, it is also a consequence of the interplay among factors shaping the local environment, which has reflected the agendas of all actors active in these areas.

The Impact of Demographics, Markets, and Security

Over the course of the Syrian conflict, the interaction between local actors and regional states has increased the autonomy of border areas in Syria’s north, south, and east, while reducing the status of Damascus as the country’s administrative center and primary source of political authority. In its place, regional powers have gained influence, eating away at the country’s sovereignty in accordance with their own priorities. Demographics, cross-border economic relations, and security have emerged as the main drivers of this policy. The interaction of each of these factors continues to shape sociopolitical patterns across Syria’s borderlands.

The Reshaping of Syria’s Demography

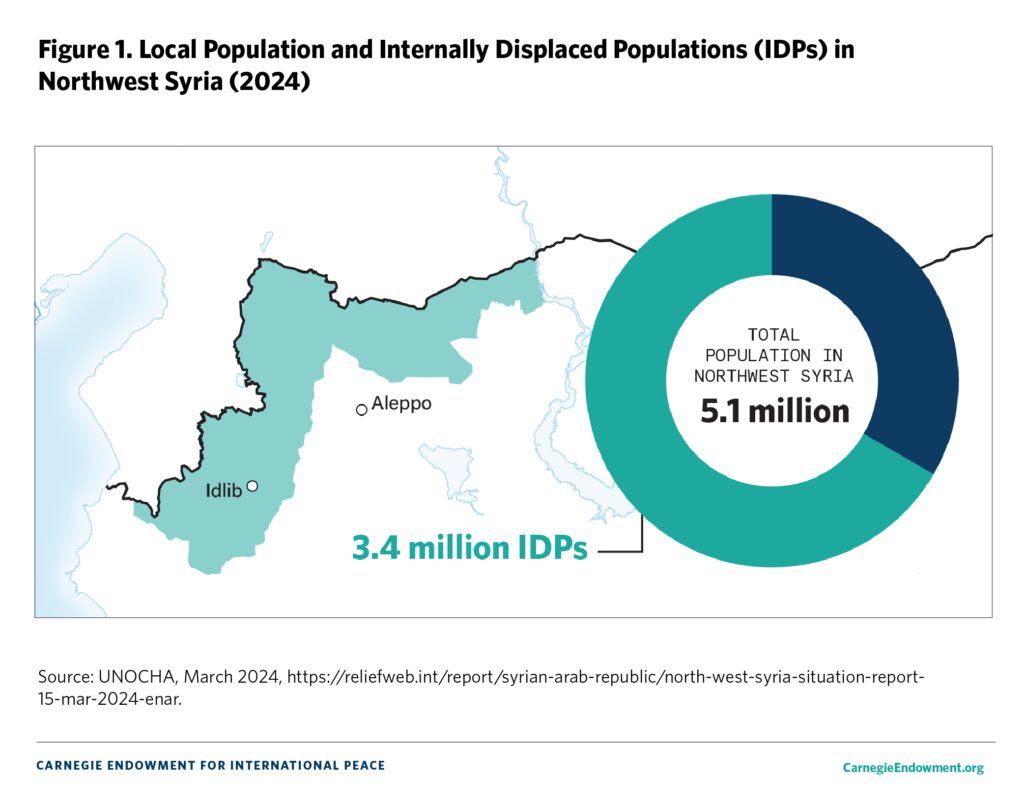

The war in Syria has radically reshaped the demographics of Syrian society. At least 14 million people have left their homes mainly as a result of conflict, while a whole new generation of Syrians has been born into a new, divided Syrian reality.33 Displacement has been caused by many factors. Some populations fled zones of conflict preemptively, others fled violence, and yet others left areas of origin to pursue better life opportunities. The situation in the Turkish, Iraqi, and Lebanese border areas each illustrates different demographic developments and their impact on Syria’s sovereignty.

Demography not only covers border areas as such but also encompasses how the different actors in Syria, particularly the Syrian government itself, have used border politics and the cross-border displacement of populations to secure political leverage and gain concessions. What is also striking in this saga is how the Syrian regime and outside actors have employed displacement as a means of conflict management. The most remarkable example is how such social engineering has shaped the sociodemographic outlook of Syria’s northwest.

With the start of the conflict, the Assad regime faced a major challenge: how to deal with a specific segment of its Sunni population seen by the regime as the social incubator of the uprising. A major general in the Fourth Armored Division, a key regime-protection unit in the Syrian army, described this population as conservative with sectarian tendencies, whose members had flawed convictions regarding the regime but remained convinced of the validity of their beliefs.34 Many in Syria’s leadership viewed these people as irreconcilable, arguing that their reintegration into society would represent a time bomb in the future.35

In 2016–2018, some 200,000 Syrians living in opposition areas recaptured by government forces agreed to be transferred to northwest Syria, notably Idlib Governorate.36 They preferred this to finding themselves at the mercy of the Syrian government and its security forces. The regime accepted this option as a way of addressing the predicament it faced of what to do with a large and antagonistic population. The regime’s move, facilitated by Russia, meant accepting the loss of control over part of its population, effectively ceding a key component of its sovereignty. Presumably, this was a temporary measure, with the intention of recapturing the northwest at a later stage in the conflict. This is evidenced by the government forces’ military campaigns in the region after 2018.37 However, the regime’s weaknesses—due to a variety of domestic political and economic factors, Russia’s focus on the war in Ukraine from 2022 onward, and disagreements with Türkiye—all came together to halt the military advances of government forces in the northwest.38

Uprooting a population from its native region has been a method of conflict management since the beginning of the war in Syria. Initially, government forces largely failed to decisively defeat populations that supported the rebellion. Even in instances where they won their battles, this often led to the displacement of communities to other locations, where they renewed fighting. The battle of Qusayr in 2013 best illustrates this pattern. In June of that year, government forces and Hezbollah were besieging rebels and civilians in the town. Exhausted and defeated opposition forces and the civilian population were allowed to leave through a corridor controlled by Hezbollah.39 Yet the rebels’ displacement to nearby localities allowed them to regroup and receive supplies from Lebanon, which set the stage for new clashes with government forces and Hezbollah.

A more complex and convoluted example occurred in Homs in 2014. The Assad regime’s victory in Qusayr severed the opposition’s supply lines from Lebanon to the old city in Homs, allowing the Syrian military to end the rebellion there.40 As government forces pressed forward and took more territory from the rebels, there were several initiatives, from the United Nations and others, to evacuate the elderly and injured and mitigate conflict, most of which failed. By mid-March 2014, there were 1,500–2,400 people still besieged in the old city.41 At that point, the negotiations encompassed Iran, Russia, and rebel groups located outside Homs. Finally, a deal was worked out that allowed the first truly organized eviction in the Syrian war, whereby those trapped in the old city were transferred to rebel-held areas in northern Homs Governorate, starting from early May 2014.42

While the example of the old city of Homs reflected demographic change, which would later be replicated elsewhere, the process was not as clear-cut as imagined. The evidence suggests that the displacement from Homs was more a by-product of several factors than the consequence of an intentional plan. These included the Assad regime’s unwillingness to reintegrate the last 1,500 people in the old city, as well as the besieged population’s refusal to put its fate in the hands of the government’s security apparatus and go through its notorious screening process. This suited both the regime, which wanted to uproot the rebellion, and the opposition, which preferred eviction to arrest and probably death.

Arguably, what occurred in Homs became a precedent for the preplanned, coordinated population transfers that came later on and that ended conflict in a number of areas. Population transfer deals became much more frequent across Syria and intensified after Russia’s military intervention at the end of 2015. Opposition-held areas began falling to government forces, mostly through agreements stipulating population transfers to Idlib Governorate, which had emerged as a stronghold for Syria’s opposition after government forces had lost Idlib city, Ariha, and Jisr al-Shughour in March and April 2015. 43

The largest transfer took place from East Ghouta, near Damascus, at the beginning of 2018. At the time, according to the United Nations, 278,000 people lived under siege in opposition-held areas of the region. 44 Once the rebels were defeated, about 66,000 people decided to depart for Idlib Governorate, while the rest were either displaced to government-controlled areas or remained in Ghouta.45 Those who left for Idlib were mainly from the rural Sunni conservative base of the anti-Assad rebellion. All men of military age had to go through a screening process, a way for the regime to capture anyone who might be a threat.46 Not all who left necessarily opposed the regime, while not all who stayed escaped the regime’s punishment. But overall, the process helped the regime uproot those who rejected its rule, while conserving those who accepted it. Ever since that time, there have been no signs of rebellion in Ghouta. Transferring the unyielding segment of the population to Idlib was not the final answer, but it was a means of conflict management that brought large parts of Syria back under government rule.

Equally important, such steps fed into Turkish plans for the northwest. Much like the Assad regime, Türkiye regarded one of the populations in its midst as a major security threat—namely the Kurds in northern Syria who supported the PKK. When it became clear that Assad would not be removed from office, Türkiye’s primary focus shifted to addressing the presence of the YPG, the PKK’s allies, on its southern border.

The transfer of Syrians to Idlib created an opening for Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to engage in some population engineering of his own and resettle Kurdish areas with displaced Arabs. This was particularly evident in Afrin, northwest of Aleppo. In early 2018, Syrian rebels, backed by the Turkish army, captured Afrin from the YPG, reportedly displacing 150,000 people from a historically Kurdish-dominated area.47 This came shortly before the regime’s operation in East Ghouta, and some of the displaced from there ended up replacing the Kurds in Afrin.48 By mid-2023, Afrin’s Kurds were a minority, constituting at best 35 percent of the 440,000 people living in the area.49 To what extent this was coordinated by Russia, Iran, Türkiye, and the Assad regime is unclear, but by removing the YPG and its social base from Afrin and allowing the influx of internally displaced from outside the town, Türkiye removed a threat of PKK activity near its border.

While Syria’s north and northwest have provided vivid examples of demographic change in border areas, demographics have also shaped developments along the Syria-Iraq border. However, this was characterized not so much by the displacement and isolation of a largely Sunni population as by its cross-border integration between 2014 and 2019, when ISIS made Sunni identity a cornerstone of its governance in these areas. In the central border region between Syria and Iraq, Arab Sunni populations on both sides of the frontier had long been connected through tribal links and kinship relations.50 The limited access of the central authorities, whether Iraqi or Syrian, to these areas created a conducive environment for the emergence of Sunni Salafi jihadi organizations. Indeed, when ISIS established its self-described caliphate in 2014, it formed a wilaya, or province, encompassing Arab Sunnis in western Anbar Governorate in Iraq and Deir al-Zor Governorate in Syria.51

The defeats of ISIS in Iraq in December 2017 and Syria in March 2019 were followed by the official reopening of Qaim-Boukamal Border Crossing in October 2019.52 However, this did not signify a return of full state authority and sovereignty; rather, the militias that had fought ISIS filled the void. Pro-Iran PMF militias succeeded in anchoring themselves in the central border area. Subsequently, the foothold these groups carved out for themselves transformed the border into a nexus for projecting Iranian regional power, through which Tehran was able to connect with its allies and proxies in Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon. As a result, the inhabitants of Boukamal and Qaim were either displaced because of ISIS activities or lost agency in the area due to the dominance of Shia militias.53

Along the northern segment of the Syria-Iraq border, a more complex scenario unfolded due to the region’s ethnic diversity and the interplay among a wider variety of political actors. Specifically, the presence of Kurdish populations in both Syria and Iraq facilitated the movement of Kurdish organizations across the border, led by the PKK, which sought to establish alternative strongholds in eastern Syria and Iraq’s Sinjar region, using the power vacuum to increase its influence and implement the vision of communitarian federalism advocated by its leader, Abdullah Öcalan, who is serving a life sentence in a Turkish prison.54

Population movement has also played a significant role with regard to Lebanon. Here, however, the Syrian regime’s exploitation of border politics by pushing large numbers of Syrians into Lebanon did not create a situation limited principally to the border area. It was also an effort to gain substantial leverage over the government of its western neighbor and the policies it adopted. The Syrian leadership and its ally Hezbollah—even if they might compete for influence in border regions, especially when it comes to security matters—are on the same page in exploiting demographics to make Beirut more compliant.

The Syrian conflict triggered a major exodus of Syrians fleeing to Lebanon. Today an estimated 1.5 million refugees reside in different parts of the country,55 of whom 784,884 are officially registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.56 This represents around 22 percent of Lebanon’s population. Most of the Syrians were forcibly displaced from areas once deemed to be the heart of the anti-regime opposition, such as Homs and Hama Governorates. Nearly 600,000 refugees live in northern and eastern Lebanon, along Syria’s border.57 Even though the pace and intensity of the Syrian conflict have subsided since 2017, the conditions for a refugee return remain difficult.58 There are significant obstacles to such a return. These include not only the behavior of the Syrian authorities and security services, who do not favor this outcome, but also the dire economic and security conditions in Syria, as well as the widespread destruction of property and expropriation of absentee property, which often means refugees have nowhere to return. The Syrian regime has also introduced regulations, including security clearances, for some refugees in Lebanon. Permission is mostly refused by the security services, 59 though Syrians have returned informally.60

With Hezbollah’s support, the Syrian regime has sought to use the presence of Syrian refugees mainly to achieve political gains in Lebanon, specifically the restoration of high-level relations and close coordination.61 This is a particularly contentious issue, given Syria’s decades-long domination of Lebanon and the fact that many Lebanese believe Syria and Hezbollah were involved in the assassination in 2005 of Rafiq al-Hariri, a former prime minister and major figure in the Sunni community. His killing led to widespread protests, followed by the withdrawal of Syrian forces after a twenty-nine-year presence. 62 Since its success in the Syrian conflict, Hezbollah has pressed for a closer relationship with Syria,63 first on the premise that this would benefit Lebanon economically,64 and second, that it is necessary in order to secure the return of Syrian refugees to their country.

In both Türkiye and Lebanon, the presence of Syrian refugees has become a cause of increasing national polarization and fueled populist mobilization against Syrians.65 The fact that many Syrians have come to Lebanon for economic reasons has led some Lebanese to argue in favor of a more security-oriented approach, which would not only seek to reduce the numbers of Syrians present in the country but also strive to end cross-border smuggling, which has been very costly for a Lebanese state already facing a severe economic crisis.66 Most importantly, the large number of Syrians has created an imbalance in Lebanon’s delicate sectarian makeup, because most of them belong to the Sunni community. The refugees have also placed a heavy burden on Lebanon’s shaky infrastructure, particularly as most have settled in poor areas, leading to conflicts over scarce resources. 67

So, while the regime in Damascus may have lost sovereignty over border areas in Syria, in Lebanon it has sought to use demographics as a means of restoring some of the power it once enjoyed in the country.68 However, the return of refugees also serves as a bargaining chip in Syria’s negotiations with the international community, both with Arab countries, with which Syria would like to normalize relations after years of isolation, and even with Hezbollah, whose rising influence in Syria has not always pleased the regime. Any progress on a refugee return will likely require important political or financial concessions in order to be carried through.

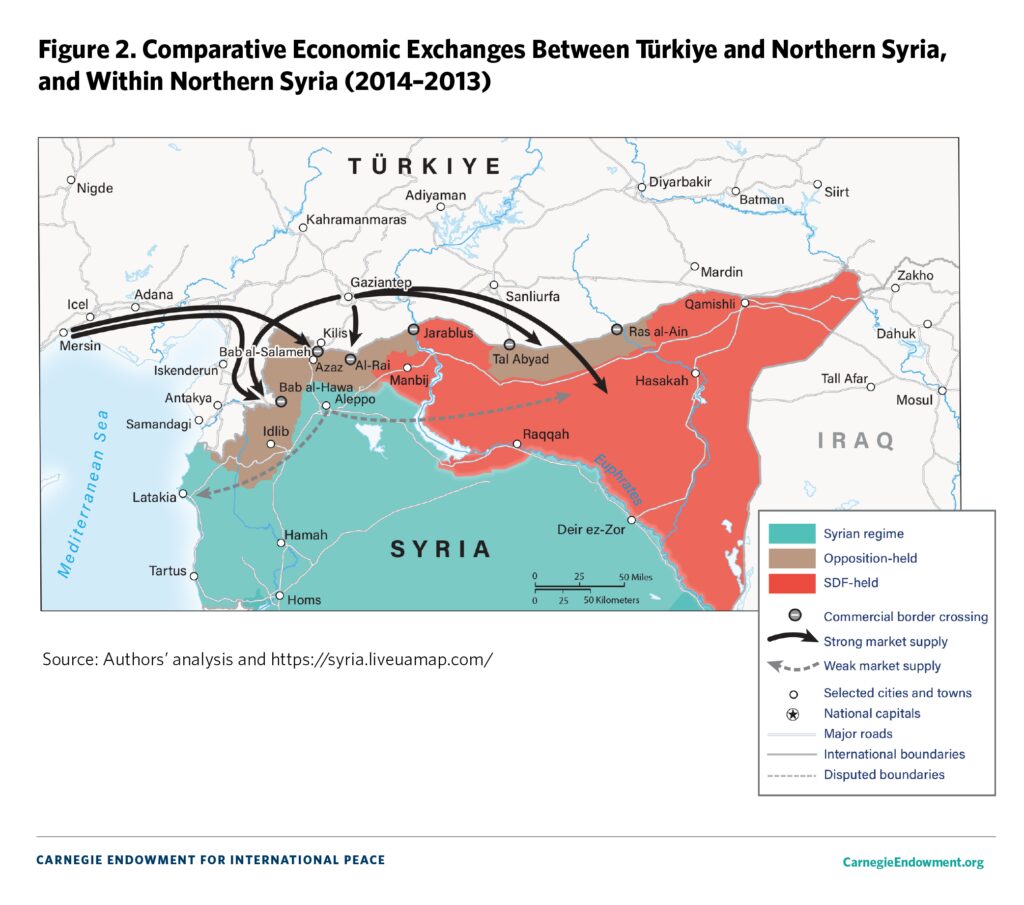

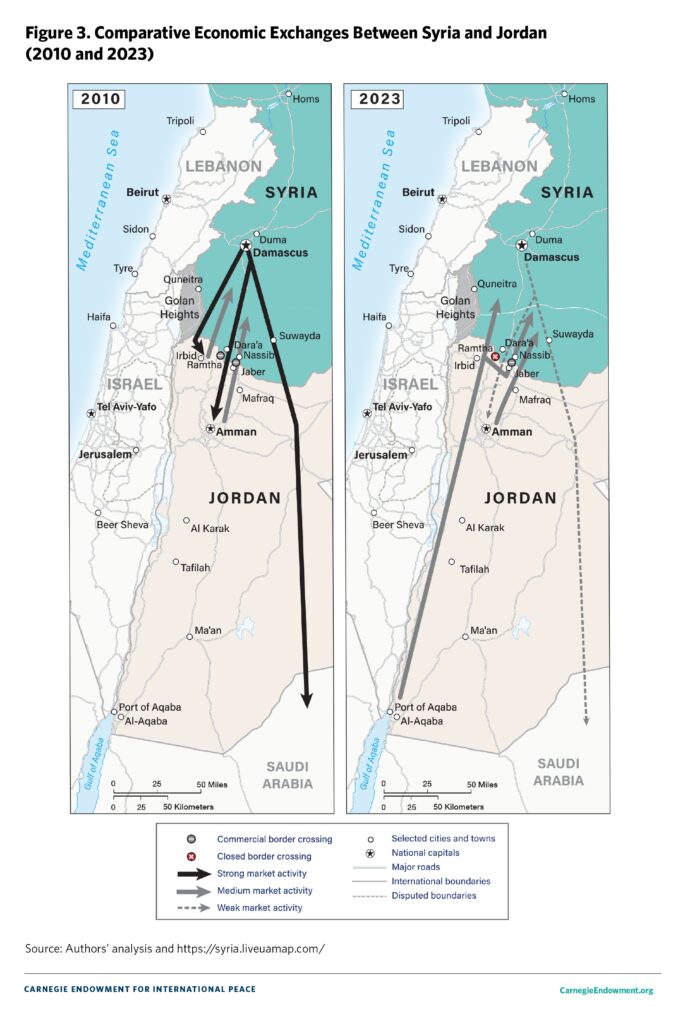

Cross-Border Economic Relations and New Markets

The Syrian conflict has had another major impact on border areas, namely reshaping cross-border economic networks while also giving rise to new economic centers and actors that are outside the Syrian regime’s control. This has been visible notably along the northern border with Türkiye, in particular through the marginalization of the regime-held city of Aleppo as an economic hub in favor of border towns that are strongly tied to Türkiye and Türkiye-based businesses. Along the Syria-Iraq border, the examples vary depending on who controls a specific area, but in all cases the situation on the ground only underscores the Assad regime’s lack of authority over the eastern borderlands.

The wartime story of Aleppo, mirroring other cities in Syria, is marked by division, death, displacement, and ruin. Aleppo stands out more than other places because, once the conflict began, this prewar economic and administrative center for the northern half of Syria was replaced by a new economic order tied to the international border.Top of FormIn 2010, one-fifth of Syria’s GDP contributions came from Aleppo Governorate.69 Commercially, goods from all over the world made their way through sea and land ports to Aleppo to be redistributed not only throughout the governorate but also beyond that to northern Syria. The workforce came from the city’s poorer neighborhoods, informal settlements in Aleppo’s eastern peripheries, or the rural hinterland where job opportunities were limited. As war overwhelmed Aleppo in 2012, however, this reality was turned on its head: capital and investors fled the city, as did its skilled workforce, and economic activities shifted toward safer border areas outside government control.70

The most prominent example is Sarmada, a border town of 15,000 people located west of Aleppo and next to the Bab al-Hawa crossing with Türkiye.71 Shielded from Syrian and Russian airstrikes because of its proximity to Turkish territory, Sarmada became a haven for displaced Syrians, so that by 2019 its population had soared to 130,000.72 Many of the displaced were poor, but along with them came investors who, mostly in cooperation with the locals, contributed to changing the face of the hitherto sleepy town. Soon, wealthier neighborhoods were being constructed, reflecting the emergence of a prosperous new class.73

Remarkably, Sarmada became a bridge connecting Syria, Türkiye, and global markets—a function that had been played by Aleppo before 2011. Notably, Sarmada acted as an economic node for Syrians who had moved their businesses to Türkiye, and the city began manufacturing goods and selling them to Syrians both inside Türkiye and in other parts of Syria.74 In 2015, 35 percent of all new firms in Türkiye’s Kilis Province had Syrian shareholders, while the figure was 15 percent for Mersin Province and 13 percent for Gaziantep Province.75 To get a sense of the expansion in commerce, exports from Gaziantep to Syria were worth $400 million in 2015, four times what they were worth in 2011.76

Sarmada also became a connecting point, mainly through the Turkish port of Mersin, between global markets and Syria. This included opposition-held northwestern Syria, Kurdish regions in the northeast, and areas controlled by the Syrian government. However, in the past few years, under pressure from locals living in opposition-held areas, internal crossings between regime-held areas and Idlib have remained closed.77 Crossings with other opposition-held areas were closed during the coronavirus pandemic and largely remained so afterward. Commerce between the northwest and government-held areas is now limited mostly to smuggling activities.78

Sarmada has also benefited from the fact that, as Bab al-Hawa became a key crossing point for humanitarian aid to Syria, supplies were stored in Sarmada’s warehouses. This aid became integral to the local economy.79 From July 2014 to November 2020, northwestern Syria received humanitarian aid delivered by 37,700 trucks, with approximately 85 percent of them entering through Bab al-Hawa.80 While the ISIS caliphate existed, Sarmada also became a transit hub for consumer goods and aid heading to ISIS-controlled areas.81

In December 2016, government forces captured the rebel-held part of Aleppo city, having earlier secured the north-south corridor connecting Aleppo to Damascus.82 Gradually, through military operations in 2019–2020, they took back territory from the rebels and recaptured some parts of the Aleppo hinterland, though they were unable to reach the Turkish border.83 Those developments gave hope to Aleppo’s residents that the city might regain some of its economic vitality. Yet Aleppo remains a shadow of its former self, with no labor force or investment and a continued brain drain and capital flight.84 Meanwhile, in the northwest, which since 2016 has effectively become a Turkish protectorate, there have been replications of the Sarmada model, with towns such as Azaz, Al-Rai, and Jarablus seeing population growth and an improvement in economic infrastructure and trade.85

Syria’s border with Iraq tells a somewhat different story. Instead of the emergence of alternative economic hubs, key parts of the border and the resources they generate have fallen under the influence of nonstate actors. The Syria-Iraq border for the most part consists of vast plains with no natural barriers separating the two countries. This has often facilitated cross-border smuggling. The cutoff in diplomatic relations between Syria and Iraq, from the late 1970s to the late 1990s, led to the rise of smuggling or informal economic relationships among local groups, often the result of cross-border tribal or family ties.86

In recent years, however, smuggling and informal economic relations have fallen under the control of nonlocal actors, including militias and armed groups, which have engaged in smuggling as part of their military activities or to maximize their resources.87 This situation persists as major border crossings, such as Qaim-Boukamal, Tanf-Walid, and Rabia-Yarubiyya, remain closed or are operating at reduced capacity under the influence of the armed groups. Today, in the hybrid security landscape of the Syria-Iraq border, the distinction between formal and informal security entities has become blurred. Determining who is the legitimate authority has become challenging as paramilitary groups have integrated themselves more deeply into local governance, security operations, and economic activities. This ambiguity mirrors the array of local, national, and broader geopolitical interests at play in the region, impacting local governance and border management.88

Militias such as Kataib Hezbollah, the Fatimiyoun, Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba, and Kataib al-Imam Ali have also adversely affected the local economy by dominating illicit activities, particularly the smuggling of fuel from Syria. Before October 2019, when Baghdad declared the official reopening of Qaim-Boukamal Crossing,89 the border was closed, but this did not prevent militias from allowing hundreds of trucks to cross for the groups’ own purposes, as well as some trucks transporting licit and illicit goods, as well as weapons. State institutions struggled to monitor areas controlled by IRGC-backed militias near the Qaim border zone, as confirmed by a member of an official Iraqi security body.90 The militias reportedly levied taxes on the trucks transporting goods.91

In some cases, militia activities have even involved taking over formal economic activities. For example, following the defeat of ISIS, an Iran-linked militia inside Syria operated the Ward oil field, located about 50 kilometers (30 miles) from Iraq. Reports suggest the militia retained a portion of the oil output, with the majority being transported to the Homs refinery as part of a deal involving the militia; a company headed by Hussam Qaterji, a businessman close to the Assad regime; and Syria’s Ministry of Oil, which manages the facility. Militias and locals connected to them also play a role in the smuggling of oil and tobacco from Iraq into Syria.92 Both examples again highlight the limited control the Syrian state has over these regions.

In the northern section of the border, AANES, which is controlled by the YPG, and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in Iraq have loosely formalized border management at their shared border crossings, as part of their efforts to assume responsibilities previously held by the governments in Damascus and Baghdad.93 Both these entities straddle the line between state and nonstate actors. There exists a robust array of cross-border activities between the two sides, including formal and informal commerce, human migration in pursuit of employment, and the movement of PKK militants and U.S. troops, among others. All these activities are occurring independently of the Syrian and Iraqi governments, which do not recognize the activities of the main crossing—known as Symalka on the Syrian side and Faysh Khabur on the Iraqi side.94 The loose formalization of relations aims to combat smuggling and illicit activities, which siphon off resources valuable to both AANES and the KRG. Nevertheless, the border region remains entrenched in conflict and institutional volatility, with political factions and their associated paramilitary groups competing for influence and control. Consequently, gray-market activities persist and in certain instances are even endorsed by the administrative authorities in the KRG and AANES.95

A notable aspect of the shifting economic landscape is the emergence of novel border crossings facilitating the movement of people and commodities between northeastern Syria and Iraq’s Kurdistan Region.96 These locations are contested sites over which the KDP and AANES have vied for political influence. Extending for approximately 150 kilometers (90 miles) along the border, this stretch begins at the nexus of the Iraq-Syria-Türkiye borders and continues southward to the Baaj District in Nineveh Governorate on the Iraqi side and Shaddadi on the Syrian side.97 In this area, there is one formal crossing, Rabia-Yarubiyya, and three informal crossings, Symalka-Faysh Khabur, Faw, and Walid (to be distinguished from another Walid crossing further south).98

Security and Syria’s Border Regions

Syria in the last decade or so has seen the establishment of a number of parallel security orders. While these differ from each other, all have undercut the Syrian state’s sovereignty and its government’s authority, particularly in border areas. They include the Turkish, Iranian, and U.S. security orders, each within specific zones of operation or influence.

The Iranian model, through the promotion of local pro-Iran militias, has connected Iraq with eastern Syria, and from there with southern Syria and Lebanon. The example of Qaim has shown how Iran has used a Sunni town as a passageway for its militias to secure regional influence, even as it has expanded its sway over some Sunni armed groups. The Turkish model has prevailed in the north, where the Turkish military is present, and has created effective self-defense zones and reshaped local power structures. The United States is present in eastern and northeastern Syria, as well as in the Tanf base near Jordan, initially as part of its participation in the international coalition to combat ISIS. For the foreseeable future, Damascus’s ability to restore its sovereignty over these border regions is nonexistent.

Unlike the northeast and northwest, the security landscape is more fluid in government-controlled areas. Rather than a single dominant model, there is dynamic overlap and competition involving Syrian government forces, Russia, and Iran.99 Russia and government forces, each for different reasons, have not succeeded in establishing a new security framework after 2016, when Moscow helped the Syrian regime recapture opposition-held areas, including Rural Damascus Governorate and the entire south. At first, the Syrian military seemed victorious thanks to Russian backing. But the Assad regime became gradually weaker in subsequent years, in part due to crushing U.S. sanctions and the collapse of a Lebanese economy that had acted as a financial lung for the ailing Syrian economy,100 and Russia refocused on the Ukraine war. As a result, Russian endeavors in southern Syria began faltering.101 Russia remains an important player, but less so than Iran, the leading actor in Syria.

The Iranian Model

Iran’s security model is still taking shape and is being challenged. The Syrian conflict created a space for Tehran to expand its military and economic networks, and its ideological reach, throughout Syria. This has reinforced the notion that Iran is a political actor with major regional influence, because of its presence near Israeli-controlled territory and along the Jordanian border. However, Iranian activities in southern Syria are not solely about confronting Israel, Tehran’s main regional antagonist. Iran is advancing a long-term and dynamic project to transform its spheres of influence in Syria’s border regions into political resources. These can be used not only as leverage against Israel, the Assad regime, Russia, and Jordan (which is effectively the gateway to the Gulf) but also in the context of negotiations over regional issues involving, but not limited to, Syria.

Given Russia’s and the Assad regime’s shortcomings, the Iranian security model remains the most viable and sophisticated in Syria. Iranian activities in the past decade in Damascus and Syria’s southern governorates—mainly Quneitra and Daraa, and to a much lesser extent Suwayda—reveal several characteristics of this model. Most notably, it works against the sovereignty of states and is supranational. The security infrastructure that Iran and Hezbollah have built in Rural Damascus Governorate and Quneitra is part of a larger security framework that connects several Iranian nodes in the region. This is reflected in the casualty list of Iranians and their allies. Many members of Hezbollah and of Iran’s IRGC, whose Quds Force has spearheaded Iranian overseas operations, have been killed in Israeli attacks in Damascus and the south, confirming they are active in those areas and have put in place the means to enable their movement between Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria.102

The Iranian model works against state sovereignty precisely because it has undermined an already weak Syrian state in favor of a supranational project. Its strength necessarily means the subordination of Syrian to Iranian interests. This ought to be a dilemma for the Assad regime, which, though it is empowered and sustained by its ally and sometimes postures as part of the Axis of Resistance, is aware that the price to pay is ultimately Syrian compliance. One example illustrating this is the higher number of Israeli violations of Syrian airspace after 2011, as opposed to before 2011, when Iran’s influence in Syria was much less.103

Another striking characteristic of the Iranian model is that it is better equipped to thrive in unstable, post conflict environments such as southern Syria. In contrast, the instability in southern Syria has taken a heavy toll on government forces. Damascus has seen its resources depleted in the south through assassinations and attacks. From the political and administrative perspectives, the south has become an example of the failure of postconflict governance. As for Russia, its ability in 2018 to broker a deal that ended rebel rule and that was acceptable to the Syrian government, the United States, Israel, and Jordan was an achievement, but little more.104 Russian officials failed to build lasting influence on the ground and, following their invasion of Ukraine, lost some of what they had gained in Syria.105

Yet the system Iran has put in place is not without its challenges, especially as Iranian militias face largely hostile populations in Daraa and Suwayda. In Suwayda, for instance, Iran attempted to form and support a Druze militia but failed due to strong local opposition from within the community.106 Israel’s few strikes in those two governorates appear to be an indication of Iran’s inability (so far) to build up a threatening presence there.107 However, Tehran and its allies have a strategic edge in that they are the only foreign actors with a security model, resources, and extensive experience in operating in chaotic settings. For instance, through affiliated militias, Iran has been able to carve out pockets of influence in Quneitra right up to the 1973 disengagement line with the occupied Golan Heights, while taking advantage of local grievances and sectarian fears that arose during the years of the Syrian conflict.108 Their sway over informal networks has also allowed them to offer protection and patronage by bringing the local population into licit or illicit revenue-generating activities.109

An essential facet of the Iranian security model is its extension to Lebanon. There, Hezbollah has played a vital role in Iran’s intervention in Syria and in the Axis of Resistance alliances stretching from Iran to the Mediterranean Sea. Significant segments of the Lebanon-Syria border, with the exception of Akkar in the far north, have long been major zones of influence for Hezbollah, through which the party has been able to move weapons and other material into and out of Lebanon.110 Following Hezbollah’s intervention in the Syrian conflict in 2012 on the side of the Assad regime, the party’s control over these borders increased further, specifically after its victory in the battle for Qusayr in 2013. Since that time, Hezbollah has become a player on both sides of the border, leading to contradictory dynamics. In Syria, Hezbollah, with its growing influence, has faced pushback from a Syrian regime reacting to its loss of sovereignty.111 But in Lebanon both have collaborated in trying to influence the Lebanese state’s behavior, even as they have exploited the border for lucrative smuggling operations.112

In light of the benefits they have derived from the border, the Syrian regime and Hezbollah have long opposed the Lebanese government’s attempts to tighten border controls. On the Lebanese side, Lebanon’s armed forces have built dozens of surveillance towers with the support of the United Kingdom in order, initially, to prevent infiltration by Salafi jihadi groups into Lebanon, monitor cross-border movement, and prevent smuggling.113 The towers have helped Lebanon’s military limit the flow of Syrian refugees into Lebanon, with hundreds detained every month in the past year.114 However, the Syrian government officially lodged a complaint with the Lebanese government objecting to the use of towers, claiming they provided the United Kingdom with intelligence on Syria.115 Hezbollah-affiliated media outlets were also openly critical.116 While such displeasure is unlikely to curtail the towers’ use, it can limit their expansion as well as technological improvements. The borders remain porous, allowing Hezbollah and other actors to operate on both sides.

Hezbollah’s role in the Iranian security architecture in Syria has fed into Tehran’s efforts to link Iran to the Mediterranean.117 During the conflicts in Iraq and Syria in the past two decades, Iran’s reach has extended thousands of miles, eating into or replacing the authority of central governments in Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon over their border areas. This has not been without incident. In 2018, three years after Moscow intervened in Syria, Russian military police were deployed to the area of Qusayr,118 provoking tensions with Hezbollah. The move reflected both the Assad regime’s and Russia’s discontent with long-term Hezbollah entrenchment on the Syrian side of the border with Lebanon. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine led to a reduction of the Russian presence in Syria generally and in border areas specifically, yet the decision of the Syrian military to reinforce its presence in the area of Qusayr in November 2023 suggested that tensions persist over Hezbollah’s reach inside Syria.119

This situation is unlikely to change soon. Hezbollah has continued to impose its presence in the border area, to the detriment of the Lebanese army and security services. At no time was this clearer than during the battles that took place in summer 2017 in the eastern border area against Salafi jihadi groups affiliated with ISIS and Al-Qaeda. Hezbollah stepped in to fight these groups alongside the army, which had launched its Fajr al-Jouroud operation, making it appear that it was as much a protector of Lebanon’s borders as the country’s armed forces.120 Moreover, Hezbollah subsequently struck a deal with the Syrian militants, allowing their transfer to northern and eastern Syria, explicitly undermining the Lebanese state and armed forces as the principal interlocutor in matters of national defense. What the episode reaffirmed was that when it comes to the border with Syria, Hezbollah is unwilling to cede significant decisionmaking capabilities to Lebanese state institutions, largely because, as in Syria or Iraq, the border is essential in the broader Iranian regional security network. Iran’s interests will continue to dictate Syria’s centrality in the Iranian regional strategy.

Iran’s security model, in which Hezbollah poses an obvious security threat to Israel, is not limited to Lebanon. In fact, the instability and the proliferation of informal criminal networks in Daraa and Quneitra is more of a Jordanian problem. For Jordan, the threat emanates from the fact that these Iran-linked networks have been engaged in illicit activities that have destabilized Jordan in several ways.121 One way is through drug trafficking, with Jordan having become a market for drugs produced in Syria. Between 2012 and 2022, cases of drug possession and trafficking by local or foreign citizens rose 150 percent from 7,714 to 19,140.122 At the same time, Jordan is also a transit point for drug trafficking to the Gulf countries, particularly Saudi Arabia, which has threatened to create problems in Jordan’s relationship with the Gulf states.123 The Jordanian authorities have also reported an increase in attempts to smuggle weapons into Jordan or through Jordan into the West Bank, which are major security concurs for the kingdom.124 From the perspective of Iran and its allies, such developments are welcome. Not only do they allow Iran’s ally Syria to build up valuable political leverage in its ties with the Gulf states and Jordan, which can be used to reintegrate Syria into the Arab world, they also harm the interests of Jordan, a prominent ally of the United States that has a peace treaty with Israel.

Jordan’s response to Iran’s security model in southern Syria has been timid in comparison to that of Israel. Since its rapprochement with the Syrian regime, Jordan has sought to cooperate with Damascus to curb the threats from Syria’s borders through several high-level meetings that have included security and military officials.125 At the same time, Jordan has also become more assertive by attacking smugglers on its border with Syria,126 at times attempting to target them inside Syria.127 It has also sought more assistance from the United States.128 Despite Jordan’s improving ties with Damascus, there has been little if any reciprocity from the Syrian side, even as the Syrian-Jordanian border continues to be a locus of instability where Iran-linked networks are best suited to thrive.

The Turkish Model

The Turkish government began supporting protests against Assad’s regime starting in the early months of the uprising. The peak of this collaboration occurred during the battle for Aleppo in summer 2012, when armed opposition groups took control of large parts of Aleppo Governorate. However, the regime responded to this by withdrawing its forces from Kurdish areas along the Turkish border and handing them over to combatants of the PYD/YPG, Ankara’s primary adversary, leaving behind a security threat for Türkiye.129

From the Turkish perspective, because of the large Kurdish population in Türkiye and Turkish fears they may seek to establish an independent state, border security is seen as an existential issue. The Turkish army has entered Syrian territory several times over the past decade, establishing pockets of control along the entire border. The ultimate aim of these interventions has been to establish a zone free of the YPG, as Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan told the United Nations in September 2019.130 Yet achieving this goal in full appears to be unrealistic in the foreseeable future because of the conflicting interests of the countries present in the area, which include Türkiye, the United States, Russia, and Iran.

The elements of Türkiye’s security model are based on demography and a direct military presence. The conflict in northern Syria, southern Türkiye, and northern Iraq is ethnically driven, involving Arabs, Kurds, and Turks. A closer look at what Ankara has built along the border in the last decade clearly proves this. The military campaigns of the Turkish army have created several zones along the border with northern Syria where Arabs dominate, thereby separating Kurdish-led military forces, mainly the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), from Turkish territories across the border. These military zones are under the direct control of the Turkish authorities and are administratively linked to the provinces on the Turkish side, namely Gaziantep, Urfa, Kilis, and Antakya.

Ethnic ties also play a major role in shaping this model. The Turkish power structure in these zones is top-down, ethnically based, and static, in that it is characterized by the presence of conventional forces, clear boundaries and frontlines, and local administrations. Syrian Turkmen, though a tiny minority, are the group most trusted among Turkish leaders not only within the context of safeguarding Türkiye’s immediate security needs but also in the long run with respect to maintaining local influence. The Sultan Murad armed opposition group, consisting mostly of Syrian Turkmen, fought against the Assad regime during the uprising, and its name reflects its symbolic identification with the early Ottoman Sultans. This relationship also goes beyond military support. For example, the Turkish Religious Endowment has selected only the Syrian Turkmen armed group in the border region of Afrin for logistical and financial assistance. 131 The Sultan Murad group is part of the Syrian National Army, which the Turks established in 2017 and in which Sunni Arab armed groups also operate.132 What makes this coalition coherent is a shared fear of the expansion of the U.S.-backed SDF.

The Turkish model has a major shortcoming in that the Syria-Türkiye border will remain a constant source of concern for Ankara in the foreseeable future. Türkiye’s border policy since 2016 has been an attempt to rectify the shortcomings of its previous strategy, which hinged on supporting Islamic political groupings in their rebellion against the Assad regime. When this failed to bear fruit, Ankara found its borders with Syria vulnerable. Since 2016, Türkiye’s revised approach allowed it to regain the initiative in the borderlands with Syria, but stabilization of the border areas is not solely in Turkish hands, nor in the hands of any single political actor in Syria. Concurrently, the Assad regime’s capacity to become a partner in controlling that border remains very limited. Türkiye also faces a dilemma in northern Syria when it comes to local governance. While a certain level of micromanagement is necessary for the Turks to achieve their security objectives, their involvement also increases Turkish responsibilities when it comes to humanitarian aid, security, stability, and governance in regions otherwise plagued by instability, radicalism, poverty, and militarism.

There continue to be attempts mediated by Russia and Iraq to mend ties between Ankara and Damascus, given their shared concern over the Kurdish threat. The rapprochement process began in 2022 through Russian mediation, though these efforts yielded no notable successes. In summer 2024, the rapprochement efforts were revived through Iraqi mediation and with Russian support. Both sides showed more flexibility than previously, with Assad stating that he was open to all such initiatives, on the condition that they respected Syria’s sovereignty.133 Erdoğan stated, “Just as we kept our ties very lively in the past—we even held talks between our families with Mr. Assad—it is certainly not possible [to say] this will not happen again in the future, it can happen.”134 At the heart of the Turkish president’s thinking was border security.

The mediation efforts may still fail due to a number of contentious issues that both sides need to resolve. If this mediation fails, Türkiye’s security model is likely to persist or even expand to protect Turkish interests. However, should the countries improve ties, it would not necessarily lead to an agreement. Rather, at best, it would signal the start of an uncertain and challenging process to reshape the security order in northern Syria. This would aim to address Turkish concerns and eliminate Ankara’s need to impose its own security model.

The U.S. Model

The presence of U.S. forces in Syria can be characterized as an extension of their presence in Iraq. Since the overthrow of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003, the U.S. military has encountered many challenges emanating from the Syrian border, notably the movement of Salafi jihadists from eastern Syria into western Iraq. Despite the withdrawal plan initiated by the Barack Obama administration in 2011, American troops remained stationed on the Syria-Iraq border. The security framework they established was primarily aimed at securing the border. Over time, the United States became increasingly involved in the dynamics of the Syrian conflict because of the emergence of ISIS, the resulting partnership with the Kurdish-led SDF, and the expansion of Iranian influence and networks in Syria.

The creation of ISIS in 2013, linking Salafi jihadi activities in western Iraq and eastern Syria, constituted a major threat to regional and international security from the heart of the Middle East. In response, the United States established a broad coalition to defeat the group. Kurdish forces, fighting under the SDF banner, allied themselves with this coalition. However, the alliance is by no means permanent or impervious to geopolitical shifts. Although the ISIS threat persists, the U.S.-SDF partnership is complicated by the fact that, while the SDF views the region east of the Euphrates River (and the border as a whole) from a post-ISIS prism, it also looks at it in light of the conflict between the PKK and Türkiye, which has been ongoing since the 1980s. In both cases, therefore, the border region is one where developments have a regional impact, as opposed to being merely a local Syrian issue.

From the U.S. perspective, securing Syria’s northeastern and eastern border with Iraq has obvious implications for Iraq. While the military priority of U.S. forces remains to prevent the resurgence of ISIS—a process that may take another decade—other calculations have emerged since the caliphate’s defeat in Iraq in 2017 and Syria in 2019. A new map of influence has emerged in territories ISIS once controlled. Moscow has established a presence in the area through the regime’s remnants in the city of Qamishli and seeks to influence local dynamics, while Tehran has expanded and connected the towns of Qaim in Iraq and Boukamal in Syria. U.S. forces and their SDF allies control the main crossing connecting northeastern Syria with Iraq’s Kurdistan region, and a U.S. base has been set up at Tanf. Consequently, the borders connecting Syria to Iraq and Türkiye have become places of clashing influences.

That is why the U.S. security model, unlike the Iranian and Turkish models, is the only one that has entered into conflict with the other two models. By and large, Iran and Türkiye have not fundamentally threatened each other’s security orders, except in the tactical and manageable links that Iran-allied militias formed with the PKK, while the Astana process was one in which the two countries coordinated over security, with Russian collaboration. The U.S. presence, in contrast, has represented a major challenge for both Iran and Türkiye, even if the two countries differ over how they might react to a potential U.S. withdrawal. The American alliance with the SDF has set limits on what Turkish forces can do in northern and northeastern Syria, while the U.S. presence along the Iraq border represents a potential strategic challenge to Iran’s efforts to guarantee the free movement of its forces and that of its allies between Iraq and Syria.

The U.S. security buildup along the Syria-Iraq border has primarily relied on local partners. Kurdish groups are considered ideal allies in the war against terrorism. They were the first victims of ISIS, and their military discipline and ability to control weapons within a unified framework have made them reliable partners. Moreover, even if it is more qualified today, the robust American presence in Iraqi Kurdistan, with a large consulate and military force, has helped underpin the U.S. deployment.135

However, a major question raised by the competing U.S., Turkish, and Iranian security orders is what the implications are for reaching an eventual resolution of the conflict in Syria. Like the demographic reality in the country and the major transformations in cross-border trade and exchanges, the fragmentation of security reflects the loss of a national framework in Syria, greatly complicating the prospect of a Syrian-Syrian understanding that would be at the heart of any termination of the Syrian conflict.

Border Regions and an End to the Syrian Conflict

Thirteen years into Syria’s conflict, which today can more accurately be described as a multifaceted crisis involving regional entanglements, one can be forgiven for thinking that the problems in the country are irresolvable. Because violence persists mainly in Syria’s border areas, over which regional and international actors have considerable sway, any resolution must include a component that addresses this reality, as well as a domestic dimension encompassing steps that help to revive a national framework for Syria. Such a framework largely disappeared during the years that have fragmented the country.

However, paradoxically, Syria’s borders have remained intact. The struggle for Syria and the instability this has generated appear to have only reinforced a belief among regional countries that the borders must be preserved, mainly so that regional rivals do not benefit from their being redrawn. Moreover, the dynamics of the conflict have been essential in reaffirming these borders. When ISIS tried to erase the Syria-Iraq border, the organization’s enemies effectively fought for a restitution of that border. As the Turkish government struggled to address the influx of Syrian refugees into Türkiye, consolidation of the border was a way of maintaining a barrier to prevent the problem from being transposed northward.

At the same time, regional conflicts have spilled over into Syria, above all Türkiye’s conflict with the PKK and Iran’s conflict with Israel. This has made it more difficult to resolve Syria’s crisis. The Türkiye-PKK confrontation encompasses Syria’s northern and northeastern border regions, as well as parts of southern Türkiye and northern Iraq. Together, these areas make up what is known as Syria’s Jazeera region—stretching from the Sinjar Mountains in western Iraq to the Euphrates River in northeastern Syria. The conflict has continued to escalate, leaving the door open for further military operations by the Turkish army in Syria’s border regions. From the Turkish perspective, the PKK threat remains present, and Ankara’s proposed solutions are essentially military- and security-based. Since the collapse of secret negotiations between Türkiye and the PKK, which began in 2009 and ended in 2015, the local reality has become even more complicated and prone to sudden flare-ups.

Any trends that reinforce Kurdish-Arab divisions put the SDF in a more difficult position, and by extension its outside sponsors in the border areas, especially the United States. This was evident in August–September 2023, when a revolt by Arab tribes against the SDF near Deir al-Zor escalated and mobilized the local population.136 Such a situation could only bolster the remnants of ISIS in resuming their activities, which pushed American forces to intervene and calm the situation.137 This situation illustrated how local developments can have major impacts on outside actors, underlining how volatile the situation in Syria’s border areas is and how the absence of state sovereignty generates instability and endless conflict.

The Iran-Israel conflict is even more dangerous, with the potential to impact not only Syria’s future but also that of the entire region. The stretch from Syria’s border with Iraq in the far east to its southern, southwestern, and western borders with Israel, Jordan, and Lebanon constitutes an IRGC zone of operations. While the Türkiye-PKK conflict is taking place at the northern edge of the Levant, the Israel-Iran conflict is occurring at its strategic core—in what Assad has called “useful Syria” (Suriya al-mufideh). Dialogue in this conflict is impossible. Both Iran and Israel are engaged in a regional power struggle, exacerbated by profound ideological differences.

Iran has supported the Assad regime for over a decade, exerting major efforts to prevent its downfall. In return, it has been able to continue bolstering Lebanon’s Hezbollah. However, the Iranian project goes further than that. Throughout the Syrian conflict, Qassem Soleimani, the late commander of the IRGC’s Quds Force, established a network of militias that transcended borders and was engaged in fighting the Syrian armed opposition and ISIS. These militias have spread across Iraq and Syria and are interconnected in a network spanning eastern Syria, Aleppo, and the outskirts of Damascus and Syria’s southern border, under the supervision of IRGC commanders. This Iranian influence and presence in certain areas of Syria, especially the south, makes a confrontation with Israel all but inevitable.

Because of the links between local actors and regional states in Syria’s border regions, any national Syrian framework for political, economic, and social life in the country has almost completely disappeared, replaced by these local-regional alliances. Reconstituting a modern Syrian nation state is simply unrealistic today, and the fact that Syria’s borders are ensnared in regional conflicts has complicated any resolution of the Syrian crisis.

There have been two main approaches for settling, or managing, this crisis. The first is a centralized approach, which involves initiating a political transition focused on rebuilding Syria’s sociopolitical order from the center in Damascus. This approach, exemplified by the Geneva process initiated in summer 2012, aims to draft a new constitution for Syria.138 UN Security Council Resolution 2254 was essential in this effort, although it was formulated in a considerably different political climate than the one prevailing in the country today. The Russian military intervention in autumn 2015 altered the balance of power on the ground, tipping it in favor of the Assad regime and its regional allies such as the IRGC and Hezbollah. This shift paved the way for the adoption of Resolution 2254 in November of that year, to halt hostilities and achieve a political settlement in Syria.

The second approach is narrower in scope and is focused on reaching local agreements in specific geographical areas, or sometimes even broader agreements over those areas, mainly based on security considerations. This was embodied in the Astana process, which began in early 2017 and included Türkiye, Russia, and Iran.139 Astana adapted to the fact that the war in Syria was taking place on multiple fronts and involved conflicting regional interests, therefore it sought to stabilize frontlines between opposition forces and the Syrian military and its allies. Today, seven years later, the results have been catastrophic for Syrians and have prevented international efforts to resolve the crisis. Local deals reached between the Assad regime and armed opposition groups have led to populations being displaced from central and southern parts of Syria to border areas with Türkiye. The process has also drawn internal boundaries, segmenting Syria and undermining any basis for agreements, such as the Genevea UN process above all, aimed at resolving the country’s crisis by reviving the center.

Both the centralized and geographical approaches have been exhausted, and the international political environment has changed since the two were first adopted. Russia has been a key player in both approaches, yet its attentions are elsewhere today, even if it has no intention of exiting from Syria. Rapidly escalating regional conflicts have the potential to consume the entire Middle East in open-ended war as the politics of the region are being shaped by security priorities. Given these realities, reinforced by divisions at the international level between the United States and Russia, any talk of putting an end to the Syrian crisis seems elusive at best. Because devising a peace plan may be a step too far at this point in time, it makes more sense to look at the prerequisites necessary for any ultimate agreement, the main objective at the moment being the adoption of measures to alleviate Syria’s collapse.

There can be no resolution of the Syrian crisis without some sort of understanding among the main regional and international powers with influence in Syria, particularly in the border areas. Yet, today, there are no indications that these powers favor a resolution over a status quo that allows them to pursue their interests independently. This approach has brought the situation in Syria to an impasse. Regardless of the goals set by each of these countries, whether the demographic security belt that Türkiye has sought to establish in its conflict with the PKK or Iran’s strategic influence beyond its borders in its battle with Israel, all have largely reached a dead end, with few achievements in the past few years.

In other words, those regional and international actors, along with their local allies, are in a delicate equilibrium. This prevents any side from making significant advances without disrupting the balance of power, allowing others to expand their influence. In theory, this situation could shift if any one of the major actors were to significantly alter its policies. Currently, there are no strong indicators this will happen. Yet should it occur, it would certainly create a power vacuum in Syria, potentially triggering a cascade of conflicts until a new status quo is established.