After a pause in popular protest during the first year of the pandemic, people are returning to the streets. This year, large and long-running anti-government demonstrations have occurred in some advanced economies where unrest is relatively rare, such as Canada and New Zealand. And in several emerging and developing economies, coups and constitutional crises have sparked widespread protests. A recent body of IMF work aims to understand the economic drivers and costs of such unrest.

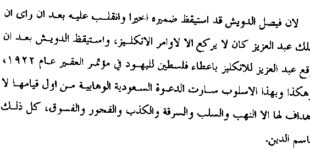

Measuring social unrest consistently is difficult. The IMF’s Reported Social Unrest Index attempts to do so by counting media mentions of words associated with unrest across 130 countries. The fraction of countries experiencing large spikes in this index, which typically reflect major unrest events, rose to around 3 percent in February. As the Chart of the Week shows, this is close to its highest levels since the onset of the pandemic.

Prior to the pandemic, unrest rose around the world. Perhaps most prominent was a wave of protest which began in Chile and swept through parts of Latin America in October and November 2019. Significant unrest also occurred at around the same time in the Middle East, notably in Algeria, Iran, Iraq, and Lebanon.

Unrest declined sharply at the start of the pandemic amid an increase in social distancing, both voluntary and mandatory. IMF research shows that this is consistent with experience during past pandemics. That is not to say that social unrest halted completely. Some significant unrest events occurred in the second and third quarters of 2020, including in the United States, which saw large racial justice protests; Ethiopia, as inter-ethnic tensions became more pronounced; and large anti-government protests in Brazil, Lebanon and Belarus.

Social unrest continued through the later stages of the pandemic, with events in both advanced and emerging and developing economies. In the former, protests erupted in places where major social unrest is usually rare, often with anti-government or anti-lockdown motives, including in Canada, New Zealand, Austria, and the Netherlands. In emerging markets and developing economies, the apparent motives for recent unrest have been more diverse, with examples including anti-government protests in Kazakhstan and Chad; a coup in Burkina Faso; regional protests in Tajikistan; and a constitutional crisis in Sudan.

Causes and costs

In coming months, two important factors could lead to an increased risk of future unrest. First, as governments relax restrictions and public concerns about catching COVID in crowds diminish, pandemic-related disincentives for protest might abate. And second, public frustration with rising food and fuel prices may increase. Although the economic causes of civil disorder are complex, and unrest is exceptionally hard to predict, steep price increases for food and fuel have been associated with more frequent protests in the past.

Any rise in social unrest could pose a risk to the global economy’s recovery, as it can have a lasting impact on economic performance. In a paper last year, IMF staff showed that unrest can have a negative economic impact as consumers become spooked by uncertainty and output is lost in manufacturing and services. As a result, 18 months after the most serious unrest events, gross domestic product is typically about 1 percentage point lower than it would have been otherwise.

Although social unrest remains low relative to pre-pandemic levels for now, the lifting of pandemic-era restrictions and the continued cost-of-living squeeze mean that protests may yet increase. This could impose significant economic costs.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News